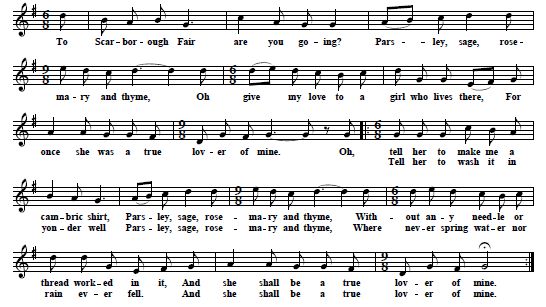

Are you going to Scarborough Fair, Paul Simon liked Carthy's version and recorded it himself in 1966 with his partner Art Garfunkel for their third LP, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme. Their recording was also used in the movie The Graduate and included on the Soundtrack-LP. Since then this song was recorded countless times by all kinds of artists. One may say that it has never been more popular than today. Carthy's version was also important for another reason. Already in the winter 1962/63 Bob Dylan heard him play this song in London Folk clubs and it became a kind of inspiration for his own "Girl From The North Country" (see also my article about this song: "...She Once Was A True Love Of Mine" - Some Notes About Bob Dylan's "Girl From The North Country"). Martin Carthy himself had learned the song most likely from The Singing Island (1960, p. 26), an influential songbook compiled by Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl. He only edited the tune and the text a little bit and dropped three of the eight verses. MacColl's recording of his version appeared in 1957 on the LP Matching Songs For The British Isles And America (Riverside RLP 12-637, also available at YouTube). According to the notes in The Singing Island he had collected this particular variant in 1947 from "Mark Anderson, retired lead.miner of Middleton-in-Teasdale, Yorkshire" (p. 109). Here are the original text and tune as sung by Ewan MacColl.

Are you going to Scarborough Fair? The following text is an attempt at unraveling the history of this song family. Carthy's and MacColl's versions will serve as a kind of focal point. But the story starts in the second half of the 17th century, presumably in Scotland.

II. The earliest documented British variant is a long ballad of 20 verses on a black letter broadside. We don't know the exact date of publication but Pinkerton in his Ancient Scottish Poems (Vol. 2, 1786, p. 496) claimed that it was "printed [...] about 1670" and as far as I can see nobody has yet come up with a better idea :

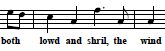

Here a young girl hears an "Elphin Knight" blowing his "Horn both lowd and shril". She wants to marry him and one night he in fact comes "to her bed". But he tells her that he would only marry her if she does a "Courtesie" to him: "shape a sark [...] Without any cut or heme [...] needle & Sheerlesse". According to Child (Vol. 5, p. 284) a "man's asking a maid to sew him a shirt is equivalent to asking for her love, and her consent to sew the shirt to an acceptance of her suitor". But for some reason she now seems to think that it wasn't such a good idea to fall in love with this "Elphin Knight" and in turn she responds by asking him to do her some favors which are equally unsolvable. In the end he confesses that he already had a wife and "seven bairns" and vanishes while the girl is glad that she got rid of him:

Songs and stories about this kind of wit contest were well known all over Europe. Child in his text about the "Elfin Knight" refers to numerous example. But it is not clear if there was a direct relationship to the British ballad or if this type of song was imported from the continent or from Scandinavia. The structure of this ballad is the same as the modern "Scarborough Fair". There are internal refrains in the second and fourth line although they are very different: no herbs and no "true love of mine". Also variant forms of verses 7, 10, 11 and 15 have survived until today. Songs of this kind were not uncommon at that time. One example is a ballad published on a broadside around 1692 that is closely related to this song family: "A Noble Riddle Wisely Expounded: Or: The Maids Answer To The Knight's Three Questions" (Pepys 3.19r, available at EBBA, see also Child I, No. 1, pp. 1-6 and Bronson I, No. 1, pp. 3-8):There was a Lady of the North-Country This structure is also known from the songs belonging to the group now commonly known as "The Two Sisters". The earliest available text - by James Smith - was published in 1656 in Musarum Deliciae, or, The Muses Recreation (pp. 169, here from a later reprint; see also Child I, No. 10, pp. 118-141, Bronson I, No. 10, pp. 143-184):There were two sisters they went playing, No reprints or other published variants of "Elfin Knight" from that time are known but it seems that the song was quite popular and well known in England. Around the turn of the century songwriter Thomas d'Urfey (1653-1723) borrowed some lines and possibly also the tune for his own "Jockey's Lamentation". This song was first published in 1706 in the fourth volume of Wit And Mirth: Pills To Purge Melancholy (pp. 99-101, here from Songs Compleat V, 1719, pp. 316-9).

Jockey met with Jenny fair The text has of course nothing to do with the original ballad. This is simply a complaint of a guy who had some problems with his girl. But the refrain is clearly derived from the older song. There is also good reason to believe that this was in fact the "pleasant new tune" originally used - and perhaps even written - for the broadside t

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

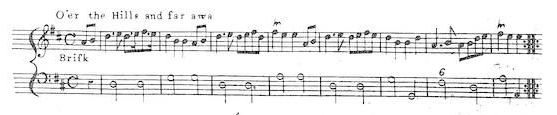

"Jockey's Lamentation" appeared again in 1787 in the first Volume of the Scots Musical Museum as "O'er The Hills And Far Away" (No .62, p. 62). In 1794 new words were written by Robert Burns ("How Can My Poor Heart Be Glad", see Dick, No. 257, pp. 234 & 451-2) and in 1805 George Thomson published this song in an arrangement by Joseph Haydn in the fourth volume of his Select Collection Of Original Scottish Airs (here in a later edition: Thomson's Collection of The Songs Of Burns [...], Vol. 4, 1825, No. 6).

III.

While the tune had a great career nothing more was heard of the "Elphin Knight" and the smart girl for a long time. But more than a century after the broadside with the earliest text a song with the title "Humours of Love" was published (Madden Ballads 2, Frame No. 1340). Unfortunately this sheet has no imprint but in the catalogue of the library of the University of Cambridge it is tentatively dated as from "1780?":

If you will bring me one Cambrick Shirt,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

Without any Needle, or Needle-work,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And wash it down in Yonders Well

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

Where never Spring Water or any Rain fell

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And hang it up on yonders thorn,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

That never bore blossom since Adam was born,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

Now you have ask'd me Questions three;

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

I hope you will answer as many for me,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

If you will take me an Acre of Land,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

.Between the Salt water and the Sea-sand,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And plow it up with one Ram's horn,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

And sow it all over with one Pepper-corn

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And reap it with a Stray of Leather,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

And bend it up with a Peacock's Feather

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And put it into a Mouse's hole,

Sweet savory grows, rosemary and thyme,

And prick it out with a Cobbler's Awl,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And when you have done and finished your work,

Sweet savory grows rosemary and thyme,

Then come to me for your Cambrick Shirt,

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

And you shall be a true Lover of mine.

From the title one may assume that this was regarded as a humorous song. It is clearly related to the old broadside. But here the background story is missing. It is only a dialogue between two persons who set each other these unsolvable tasks. But on the other hand the text is very close to the modern "Scarborough Fair", it includes all its major elements. The refrain in the second line consists of a list of herbs. Here its "sweet savoury" instead of parsley and sage, but the other two - rosemary and thyme - are identical. Also the refrain in fourth line is more or less the same. Seven of the nine verses would appear with only minor variations in the version recorded by Ewan MacColl in 1957.

Most interesting is the term "cambric shirt". Cambric linen - also called "batiste" - was "one of the finest and most dense kinds of cloth" (see Wikipedia). It may have been invented in the town of Cambrai - a part of France since 1677 - some centuries earlier. In England "cambric" or "cambrick" were more or less unknown until the early 18th century, at least judging from the fact that they only very rarely appeared in the newspapers of that time (according to my research in the 17th & 18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers). Import to Britain was prohibited during the 18th century not only to save the trade balance - it was very expensive - but also to protect their own attempts to produce this kind of cloth from Indian cotton, the so-called Scotch cambrics. Only during the second half of the century, especially since the 1770s, these terms were becoming more and more common. There is good reason to assume that the "cambric shirt" was only introduced into the song at around this time and refers not to the French but to the Scotch product .

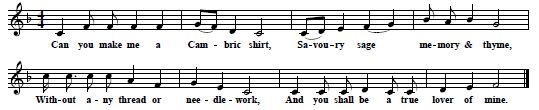

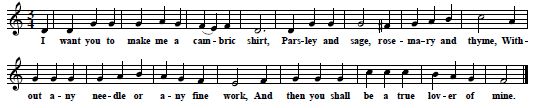

Another text from the 1780s was published in Gammer Gurton's Garland; Or, The Nursery Parnassus. A Choice Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses. For the Amusement of all little good Children, Who can neither read or run. This book of nursery songs and rhymes was compiled by the legendary antiquary Joseph Ritson (1752-1803; see Bronson 1938) first came out 1783 or 1784 and then afterwards it was reprinted a couple of times. Unfortunately we don't know where Mr. Ritson found this song. It could have been in London where he was living. But he also used to collect in Northumberland. This variant is even more closer to the modern "Scarborough Fair" (here from the 1866 reprint of the edition from 1810, pp. 4-5) :

Can you make me a cambrick shirt,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Without any seam or needle work?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Can you wash it in yonder well,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Where never sprung water nor rain ever fell?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Can you dry it on yonder thorn,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Which never bore blossom since Adam was born?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Now you have asked me questions three,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

I hope you'll answer as many for me.

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

Can you find me an acre of land,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Between the salt water and the sea sand?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

'Can you plow it with a ram's horn,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

And sow it all over with one pepper corn?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

'Can you reap it with a sickle of leather,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

And bind it up with a peacock's feather?

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

'When you have done, and finished your work,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Then come to me for your cambrick shirt.'

And you shall be a true lover of mine.

The relationship to "Humours of Love" is not clear. The verse with the "mouse's hole" is missing and the herbs in the second line are now "Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme". If the publication date of the song-sheet is correct it could be a slightly abbreviated and edited variant of that text. Of course it is also possible that both versions are descendants of an older, undocumented precursor. But it is also important to note that this particular variant must have been immensely influential for the further development of the song. Behind most popular "Folk-songs" is a printed text and in this case one may assume that countless children during the next 100 years have heard these verses from their teachers or parents or even have read it themselves.

Interestingly we also have a third variant of this song from this time. It was published in July 1807 in the Scots Magazine (Vol. 69, pp. 527-8, available at Hathi Trust Digital Library):

[He:]

As I gaed up to yonder hill,

(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh,and thyme,)

I met my mistress her name it was Nell,

" And lass gin ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll mak' to me a camric sark,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh,and thyme,)

"Without either seam or needlewark,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll wash it out at yonder well,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh,and thyme,)

"Whar water ne'er ran, nor rain ne'er fall,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

[She:]

"Now, Sir, since you speir't me questions three,

(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"I hope you will answer as mony for me,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll plough to me an acre o' land.

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"Atwixt the sea beet, and the sea sand,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll till it a' wi' yon cocklehorn,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"And sow it all o'er wi' a handfu' o' corn,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll cut it a' down wi' a dacker o' leather,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"And lead it a' in on a peacock's feather,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"Ye'll thrash it a' wi' a cobbler's awl,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"And put it a' up in a mouse's hole,

"And that an' ye be a true lover o' mine.

"And, Sir, when ye hae' done your work,

"(Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh, and thyme,)

"Come to me and get your camric sark

"And syne ye shall be a true lover o' mine."

This version was sent in by someone who called himself Ignotus. It was part of an interesting text about old Scottish ballads and served as an example for songs "a little inclined to the humorous and witty". According to the writer it "may justly lay claim to great antiquity" because he "had it from a person who heard it repeated to him when a youth by his grandfather; who also was acquainted with it in his early years". Mr. Ignotus' variant is not complete. The third task for the woman - to dry the "sark" - is missing. But it may represent the original Scottish precursor of both "The Humours of Love" and the text in Gammer Gurton's Garland. In this case it would have been the first use of the term "cambric" in a song from this family. In fact it is not unreasonable to assume that the "cambric shirt" was first introduced into this ballad in Scotland. As already mentioned this kind of linen was usually called "Scotch cambrics" because it was produced there.

It is also interesting to note that this version has an introductory verse. But there is no messenger as in the modern "Scarborough fair". Instead it describes a situation where the man and woman meet on a hill. This may be a relic of the old ballad. One may remember the "Elphin Knight" used to sit "on yon hill". But here the background story is condensed down to one verse. It is not a meeting between a supernatural being and a girl. Here the two protagonists are simply a male and a female without any further explanation.

IV.

At this point we have three versions including the "cambric shirt" but with three different sets of herbs. But where is the messenger who is sent to the girl to give her the tasks? What is the relationship of these three texts to the black-letter broadside about the "Elphin Knight"? No more contemporary sources are available. But soon a new wave of Scottish ballad collectors set out to save these old songs from oblivion. Most important in this respect were George Ritchie Kinloch, William Motherwell and Peter Buchan who all published important and influential collections in 1827/8. Professor Child had access to Kinloch's and Motherwell's manuscripts and some of the variants he found there and then included in his English And Scottish Popular Ballads can help to close some gaps.

For example it is not unreasonable to assume that the messenger had already played a role in earlier versions of this song. In the 1820s Kinloch wrote down a variant called "Lord John" from a Scottish singer named Mary Barr (Child I, 2F, pp. 17-8):

|

Here a messenger is shuttling between the two protagonists and in fact it's quite a long trip from Berwick to Lyne. One may assume that these are the Scottish towns. First the man sends him to the "handsome young dame", in this case apparently a former lover. The term "dame" as well as the title of the song - "Lord John" - suggest that the story is set in the higher echelons of society. Then she sends him back with her requests. How the story ends is not known. Why the messenger was introduced is not clear. He makes it all a little more complicated. The refrain in the second line looks a little bit strange: "Sober and grave grows merry in time" sounds like a terribly corrupted form of the list of herbs from "Cambric Shirt".

It is not known how old this variant was when Kinloch wrote it down. But Mrs. Barr's text seems to be derived from a version of the song that predates "Humours of Love" as well as the variants from Gammer Gurton's Garland and in the Scots Magazine. It may in fact represent an earlier version because there is no "cambric shirt" in this song, instead it is a "holland sark". According to Kinloch she had told him that "she never committed anything to memory that she found in print; all the ballads and songs she can repeat were orally communicated to her, upwards of fifty years ago, since which time she has not attempted to burthen her memory with learning any others" (quoted in Buchan 1972, p. 67).

Interestingly we also have two American texts from around the same time that are closely related to Mary Barr's variant. One - "as sung to him by his father in 1828, at Hadley, Mass." - was sent to Child by the Rev. F. D. Huntington, Bishop of Western New York. Mr. Huntington, Sr. had apparently learned this song "from a rough, roystering 'character' in the town" (Child I, 2J, p. 19):

Now you are a-going to Cape Ann,

Follomingkathellomeday

Remember me to the self-same man.

Ummatiddle, ummatiddle, ummatallyho, tallyho, follomingkathellomeday

Tell him to buy me an acre of land,

Between the salt-water and the sea-sand.

Tell him to plough it with a ram's horn,

Tell him to sow it with one peppercorn.

Tell him to reap it with a penknife,

And tell him to cart it with two mice.

Tell him to cart it to yonder new barn,

That never was built since Adam was born.

Tell him to thrash it with a goose quill,

Tell him to fan it with an egg-shell.

Tell the fool, when he's done with his work,

To come to me, and he shall have his shirt.

This is only the second half of the song: the girl sends the messenger back to the man. Cape Ann is a town in Massachusetts. There are two other innovations not in earlier British versions: the rhyme goose quill/egg-shell in the penultimate verse and the "fool" in the last verse - obviously the American girls were not as polite as her Scottish and English sisters. The refrain looks absurd, but in fact it is not. One should remember that in the "Elphin Knight" it was "Ba, ba, ba, lilli, ba". These kind of nonsense lines are not untypical for this song family. The only difference is that also the "true love of mine" in the fourth line is replaced by what looks like a very early example of scat vocals.

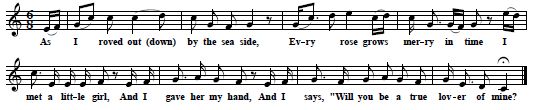

Even more interesting is an American songsheet first printed ca. 1830:

- Love-letter & Answer, And Father, Jerry, & I, Sold wholesale and retail by L. Deming South side Faneuil Hall, Boston. [n. d., ca. 1829-31, see WorldCat; reprinted in Boston by Hunts & Shaw, ca. 1836-7, see Kittredge 1917, p. 284] (available at America Singing: Nineteenth-Century Song Sheets, LOC, as108140)

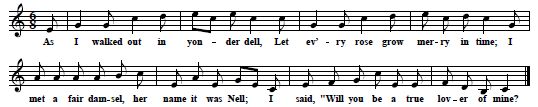

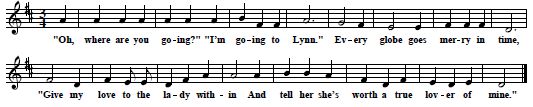

This is a surprisingly complete variant and the hand of an editor is clearly visible. But it also obvious that this text must have been derived from the same precursor as Mary Barr's ballad. Here the refrain is "Every rose grows merry and fine". This makes a little more sense than Mrs. Barr's "Sober and grave grows merry in time" and it may be the original line. The American texts are localized in Massachusetts. Lynn of course sounds similar to the Scottish Lyne:

|

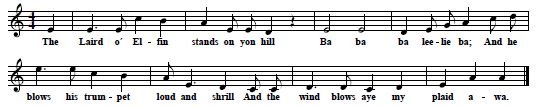

These three variants from the 1820s are of great help in reconstructing an earlier stage of the song's development. But some of the texts collected by Motherwell, Kinloch and Buchan during the same decade may also give some more hints about the early history of this song family. For example we can see that the old black-letter broadside must have been available in Scotland because Motherwell has collected a fragment of five verses that is clearly derived from that text (Child I, 2E, p. 17):

The Elfin Knight sits on yon hill,

Ba ba lilly ba

Blowing his horn loud and shill.

And the wind has blawn my plaid awa

'I love to hear that horn blaw;

I wish him [here] owns it and a'.'

That word it was no sooner spoken,

Than Elfin Knight in her arms was gotten.

'You must mak to me a sark,

Without threed sheers or needle wark.'

Also notable is another text from Motherwell's manuscripts. According to Child (I, 2I, pp. 18-9) it was from "the recitation of John McWhinnie, collier, Newton Green, Ayr" . The refrain is a little bit different from the broadside but in no way more meaningful: "He ba and balou ba". More important is the background story. Here the protagonists are a lady "on yonder hill" who had "musick at her will" and an "auld, auld man/With his blue bonnet in his han", the latter maybe the devil:

|

In fact this is a composite version. Only stanzas 3 - 15 were from Mr. McWhinnie. Thomas Macqueen wrote them down in 1827 and this text is now available in Emily Lyle's edition of the Andrew Crawfurd's collection of ballads. Both Crawfurd and Macqueen collected songs for William Motherwell (see Lyle 1995, pp. xxii-xxiii; No.84, pp. 6-7; Lyle 2007). Macqueen found the first two verses two years later, his source was Mary O'Meally from Kilbirnie (Lyle 1995, pp. xxxvi-xxxvii). Motherwell then combined these two parts in his manuscript. If they really belonged together is not clear.

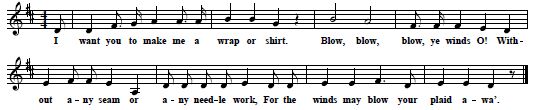

Peter Buchan also published a version in his Ancient Ballads and Songs of The North Of Scotland (Vol.2, 1826, pp. 296-8, also Child I, 2D, p. 17). I must admit that I am very skeptical about this text. It doesn't sound right and it looks as if it was collated from different variants. The first verses with the "Elfin knight" is surely borrowed from the old broadside. But at least there is another new refrain line that seems to be authentic: "Blaw, blaw, blaw winds, blaw". It will crop up again much later in American variants from oral tradition.

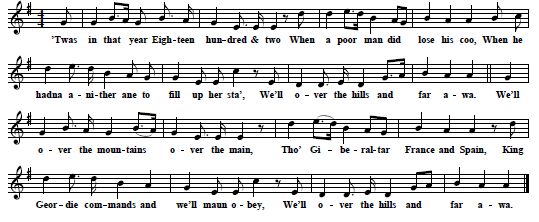

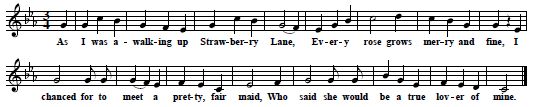

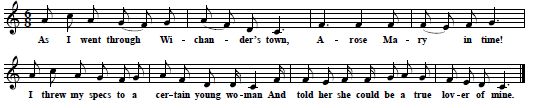

But most interesting is a version collected by George Ritchie Kinloch from the "recitation of M. Kinnear, a native of Mearnsshire, 23 Aug., 1826". The text published in 1827 in his Ancient Scottish Ballads (pp. 145-152, also Child I, 2C, p. 16) is misleading because it was doctored a little bit. Child saw the the original text in Kinloch's manuscripts and noted that four verses - 3, 10, 14, 17 - "are evidently supplied from some form" of the old broadside (Child I, p. 484). Especially important is the fact that verse 3 with the "elfin knicht" was amongst the unnecessary additions. The male protagonist was simply a "knicht" who also happened to blow his "horn loud and shill [sic!]" while standing "at the tap o yon hill". But there is no evidence that he had any kind of supernatural abilities. Here is - reconstructed with the help of Professor Child's notes - the text with the original 14 verses as performed by Kinloch's informant :

|

The refrain for the second line is "Oure the hills and far awa" instead of the nonsense syllables known from the broadside text. This looks more appropriate and would also explain much better why the tune used by d'Urfey was called by that name. The tasks are more or less complete. Here the girl has to sew the shirt "needle-, threedless" and then wash and dry it. The latter two were missing on the broadside. There is good reason to assume that this variant is much closer to a hypothetical original text of this song, the one that possibly had served as the starting-point for the editor of the broadside.

V.

Now it may be the time for a first attempt to reconstruct this song family's history. Unfortunately until now we only have one half of the songs. Not a single tune is known, with the exception of "Over The Hills And Far Away" that may have been connected with this group of ballads. The available texts represent two distinctively different types of sources. First there are the commercial products, the broadsides. There were only two of them: the black-letter broadside from the second half of the 17th century and "Humours of Love" that was published more than a century later. Their publication suggests that the song was popular at that particular time and they may also reflect what was sung by the people. But one may assume that the editors and publishers also tried to "improve" the text and brought in some variations. These versions in turn had a certain influence on oral tradition.

Then we have the works of the collectors and antiquaries who tried to save the "old ballads" from oblivion. They all had their own agenda and were not interested in what was popular but only in particular genres. Unfortunately they only rarely collected the tunes and were content with the words. Their informants were usually old people from rural areas and what they remembered were often only fragments. But this approach lead to some helpful results. What the ballad-hunters heard and then wrote down often reflected an earlier stage of the song's development. But on the other hand they were also often eager to "improve" their texts for publication and regularly doctored their ballads. In fact their works represent a different body of tradition. What at first looks like a "folk ballad" is in fact often a "folklorists' ballad".

It is not clear if the books of the collectors had any effect on oral tradition. They were of course aimed at a different target group than the broadsides and may have usually not reached those who later served as informants for the next generation of song collectors. The only exception was Ritson's Gammer Gurton's Garland. This book became quite popular and was reprinted regularly. I tend to think that teachers and other intermediaries carried at least some of these nursery songs and rhymes back to the people.

At this point we know that several types of this song existed side by side. They represent different stages of its development. But what we have are only snapshots but in no way a representative cross-section. Nonetheless the available texts allow at least some conclusions. Of course much of it is guessing work, just like a puzzle where 95% of the parts are missing.

First there must have been some kind of early version - let's call it type I - that circulated orally before the black-letter broadside was published in the 1670s. The incomplete variant collected by Kinloch in the 1820s (Child 2C) should be regarded as a relic of this hypothetical original text. The refrain in the fourth line surely was something like "the wind has blown my plaid away" while the one for the second line may have been "over the hills and far away". Two more alternate phrases for the second line were also circulating. First a nonsense refrain like "Ba ba lilly ba" or "He ba and balou ba" or something similar. Of course that one was not written in stone and I presume there were many variations. On the other hand there was also "blaw, blaw, blaw winds, blaw" á la Buchan's text (Child 2B). Which of them was the original refrain line is not clear.

The original text was of course made up of the classic dialogue between the two protagonists. First the girl is asked to sew the "shirt" or "sark" and then to wash and dry it. She responds with a set of tasks for the man and at the end she tells him that he will get his "sark" when he his "wark is weill deen". The background story is delineated in the first few verses. It seems that the man originally was a knight, about the girl we at least learn that she has a sister who "was married yesterday". Other introductory verses may have also existed, like those where the male protagonist is an "auld, auld man", presumably the devil. (Child 2I).

The text on the broadside was most likely derived from this hypothetical original version. The editor dropped some verses, especially two of the tasks for the girl. The last two stanzas don't make much sense (see Child I, p. 13) and were possibly inserted by this editor. But he also turned the knight into a supernatural being. Child (I, p.13) has noted that "the elf is an intruder" who doesn't belong to this story. Why he then called this song family "Elfin Knight" is a little difficult to understand. I assume it was because the broadside was the earliest available text. Nonetheless this is somehow misleading.

As already noted this ballad must have been quite popular around the turn of the century. Both the "original" and the broadside text were most likely written in Scotland but they migrated southwards and were surely also known in London. There either the original version or the broadside became the inspiration and source for a modern popular song, d'Urfey's "Jockey's Lamentation".

It seems that some time during 18th century a new version of the old ballad came into being. It had a new refrain in the fourth line: "the wind has blown my plaid away" was replaced by "Then he/she will be a true love of mine" or something similar. Two subtypes are clearly identifiable. The first - I'll call it IIa - had as the refrain in the second line a phrase like "Every rose grows merry in time" or variations thereof. The "cambric shirt" was not yet part of the song. But most important was a new background narrative: in the first verse an unidentified male protagonist sends a messenger to a girl who relayed the tasks to her. She in turn sends him back to tell the man what he had to do before he can get his shirt. In fact the dialogue has remained stable.

This subtype is represented by Mary Barr's variant (Child 2F) and the two American texts - Child 2J and the songsheet from Boston -, all from the late 1820s. Of course it not clear if Berwick and Lyne in Scotland were the town names used in the hypothetical original version of this type. "Lyne" isn't particularly successful as a rhyme word for "dame" in the third line. At least Lyne must have been part of the variant that had migrated to North America where then it was changed to Lynn, a town in Massachusetts. But the editor of the songsheet also had some problems with the rhymes: "Lynn" doesn't fit to "woman". These kind of rhyming problems strongly suggest that originally the first verse must have looked a little bit different.

It is also not clear what kind of shirt the girl had to sew. In Mary Barr's text it is a "holland sark" and in the Boston songsheet it remains unspecified. The American text also has a new second verse that is not known from older versions. Here the girl's first task is to weave "a yard of cloth". But it seems that this stanza was also introduced to the song in Britain. There is one variant collected by H. E. D. Hammond in 1907 in Dorset where the man asks her to to buy him "a yard of broadcloth" and then make him "a shirt out of that" (see HAM/4/31/16, p. 4 & 5, available at The Full English Digital Archive).

Interestingly the fragment from Bishop Huntington's father (Child 2J) also shows that at least in the USA the new refrains were sometimes dropped in favor of nonsense phrases. They must have been some kind of relic from the earlier type of the song. In fact it is not that far from "He ba and balou ba" to "Ummatiddle, ummatiddle, ummatallyho" and there is also not much difference in "meaning".

Of course we don't know who has created the original version of this subtype. It was surely very influential and successful. Otherwise it wouldn't have spread so far. One would expect a printed text as the starting point of this line of tradition. But by all accounts there was none and the song was at first disseminated only orally. It was printed for the very first time in 1830, most likely a couple of decades after its introduction, but only in the USA and not in Britain.

The second clearly identifiable subtype - it should be called IIb - also spread only by oral transmission and - like the first - most likely was created in Scotland. This type is represented by the variant published in the Scots Magazine in 1807. As mentioned above Mr. Ignotus claimed in his article that "he had it from a person who heard it repeated to him when a youth by his grandfather" who also apparently had learned it in his youth. Of course the text may not be exactly like the one known by said grandfather and something could have been lost or added over the intervening years. But there is good reason to assume that the distinctive elements of this subtype have remained intact.

The first verse offers a new background story. There is no messenger sent out to the girl. Instead this time the male protagonist goes "up to yonder hill". This may be influenced by the early versions of this song where the knight was "sitting on a hill". But this time he meets "his mistress" there and she even has a name: Nell. In this variant we also find the "cambric shirt" and a list of herbs as the refrain in the second line. Here we get "Saffron, sage, rue, myrrh and thyme". But it seems that they were a late addition. At least there are also other variants of this group where the refrain is more like the one we know from subtype IIa. In a version collected by Motherwell in the 1820s it is more of a mixture between the two phrases: "Every rose grows merry wi' thyme". This looks like a good advice for gardeners. Interestingly this variant also includes Nell although the introductory verse is a little bit different (Child I, 2H, p. 18):

'Come pretty Nelly, and sit thee down by me,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

And I will ask thee questions three,

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must buy me a cambrick smock

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Without any stitch of needlework.

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must wash it in yonder strand,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Where wood never grew and water ner ran

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must dry it on yonder thorn,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Where the sun never shined on since Adam was formed.'

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Though hast asked me questions three;

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Sit down till I ask as many of thee

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must buy me an acre of land

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Betwixt the salt water, lover, and the sea-sand

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must plow it wi a ram's horn,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

And sow it all over wi one pile o corn

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must shear it wi a strap o leather,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

And tie it all up in a peacock feather

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'Thou must stack it in the sea,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

And bring the stale o 't hame dry to me

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

'When my love's done and finished his work,

Every rose grows merry wi' thyme

Let him come to me for his cambric smock.

And then thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

Another closely related Scottish variant was published by the Rev. William Findlay in 1869 in Notes & Queries (4th Ser., Vol. 3, p. 605). He had collected it during the 1860s. His informant was one "Jenny Meldrum, Framedrum, Forfarshire". Child included it as variant 2M in his English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Child I, 2M, pp. 484-5; V, p. 206). This text is very similar to the version from the Scots Magazine although it was written down nearly 60 years later. The girl's name is still Nell. In fact she is mentioned by name in the three earliest available variants of this subtype. This strongly suggest that she was there from the start. Not at least hill/Nell is a reasonably usable rhyme. Here Miss Nell gets four tasks instead of three: she also has to bleach the "cambric sark". The refrain is closer to the one used for the other subtype but we have to do without the herbs: "Every rose springs merry i' t' time":

As I went up to the top o yon hill,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

I met a fair maid, an' her name it was Nell,

An she langed to be a true lover o mine.

'Ye'll get to me a cambric sark,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

An sew it all over without thread or needle,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll wash it doun in yonder well,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

Where water neer ran an dew never fell,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll bleach it doun by yonder green,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

Where grass never grew an wind never blew,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll dry it doun on yonder thorn,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

That never bore blossom sin Adam was born,'

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Four questions ye have asked at me,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

An as mony mair ye'll answer me,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll get to me an acre o land

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

Atween the saut water an the sea sand,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll plow it wi' a ram's horn,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

An sow it all over wi' one peppercorn,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll shear it wi' a peacock's feather,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

An bind it all up wi' the sting o an adder,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'Ye'll stook it in yonder saut sea,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

An bring the dry sheaves a' back to me,

Before that ye be a true lover of mine.

'An when ye've done and finished your wark,

Every rose springs merry in' t' time,

Ye'll come to me, an ye'se get your sark.'

An then shall ye be true lover o mine.

Besides these two subtypes outlined here we also have the two printed variants from the 1780s - the broadside with "The Humours of Love" and the text from Gammer Gurton's Garland - that only consist of the dialogue between the two protagonists. There is no introductory verse to create a narrative framework. On first sight it looks as if they could have been derived from earlier versions of the subtype IIb. But this would imply that the songs of this family evolved in the course of a century in a process of stepwise reduction or simplification from grand ballad to nursery rhyme: first a long ballad of 19 or 20 verses, then shorter versions where the background story is reduced to one verse and at last the decapitated variants where only the dialogue is left. But that seems to me too simple an explanation and maybe also misleading.

The dialogue between the two protagonists is the song's core and it has always remained surprisingly stable except that at some point a new set of internal refrains was introduced. This dialogue could easily exist in its own, without any introductory verses. Otherwise it wouldn't have been printed that way on a broadside nor included in Gammer Gurton's Garland. Much later, in 1890, English collector Sabine Baring-Gould was informed by a correspondent from Cornwall that this song used to be "enacted in farm houses. A male going outside and entering the room, and a female seated is addressed by him". The man sings the first half and then she replies with the set of requests he has to fulfill before he gets his cambric shirt (see Baring-Gould, Fair Copy CXXVIII, SBG/3/1/629, available at The Full English; see also Child IV, pp. 439-440). In fact this is the only reliable and reasonable contextual information we have about this song.

A game like this may have been used to affirm gender roles in a rural society: the woman has to take care of the clothes while the man has to work outside and plough the field. But on the other hand these kind of insolvable tasks could have also been a way of making fun of the excessive demands some adolescents might have of their future spouses. Not at least this song may have helped the girls to show some self-consciousness: before the man has the right to ask too much of her he better try to accomplish something special himself. There is no reason to exclude the possibility that this dialogue was used in a similar way much earlier. The anonymous ballad writers - whoever that was - could have then utilized it as a core for a longer narrative song by outlining a background story with the help of new introductory verses: the knight on the hill blowing his horn and then visiting the girl who had fallen in love with him; the messenger shuttling between the protagonists, presumably two former lovers; the man going up to "yonder hill" to meet his mistress. Other plots may have existed, too.

In fact these background stories all sound a little forced to me, as if they were grafted onto the dialogue to explain why the song's protagonist have to set each other these kind of insolvable tasks. They are never really convincing and I wouldn't regard them as masterpieces of song-writing. If in turn the dialogue is a relic of another earlier undocumented ballad is another question that is impossible to answer.

VI.

For the next 50 years not much was heard of the songs from this family. 1841 saw the publication of the first edition of James Orchard Halliwell's Nursery Rhymes of England, Collected Principally from Oral Tradition in a small print run for the Percy Society of which Mr. Halliwell - later a noted Shakespeare scholar - was a founder member (available at Google Books; for more about Halliwell see Gregory 2006, pp. 113-122). A second, expanded edition followed in 1843 and in the preface he noted that it had been his intention "to form as genuine a collection of the old vernacular rhymes of the English nursery as he possibly could, without admitting any very modern compositions, at least none belonging to the present century" (p. vii). In fact this was an impressive work that remained the standard collection for this particular genre for a long time.

"Cambric Shirt" was among the pieces that were added to the second edition (No. CCCLIV, pp. 191-3). The text used here was not from "oral tradition" as the subtitle may suggest but taken straight out of Gammer Gurton's Garland. Halliwell made this variant even more popular and more accessible. A year later another collection, Nursery Rhymes, Tales and Jingles published by James Burns in London, was criticized by a reviewer for leaving it out (see Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 7, 1845, p. 4, at BNA). But the text can be found for example in Felix Summerly's Traditional Nursery Songs of England (2nd ed, London 1846, pp. 8-9).

Another old acquaintance also found a new home in Halliwell's huge tome (No. CXIII, p. 79-80). The poor guy from D'Urfey's "Jockey's Lamentation" had mutated into Tom the Piper and then spent the rest of his long life in a nursery rhyme:

Tom he was piper's son,

He learn'd to play when he was young,

All the tunes that he could play,

Was "Over the hills and far away;"

Over the hills and a great way off,

And the wind will blow my top-knot off.

[...]

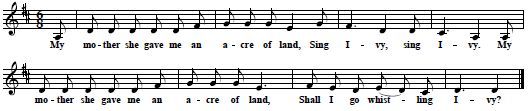

But even more interesting is another related piece that was included in this collection, but only since the 5th edition (1853, here from the 6th ed., No. 109, p. 161; also Child I, 2K, p. 19):

My father left me three acres of land,

Sing ivy, sing ivy;

My father left me three acres of land.

Sing holly, go whistle and ivy.

I ploughed it with a ram's horn,

Sing ivy, sing ivy;

And sowed it all over with one pepper corn.

Sing holly, go whistle and ivy.

I harrowed it with a bramble bush,

Sing ivy, sing ivy;

And reaped it with my little penknife.

Sing holly, go whistle and ivy.

I got the mice to carry it to the barn,

Sing ivy, sing ivy;

And thrashed it with a goose's quill.

Sing holly, go whistle and ivy.

I got the cat to carry it to the mill;

Sing ivy, sing ivy;

The miller he swore he would have her paw,

And the cat she swore she would scratch his face.

Sing holly, go whistle and ivy.

This is an example for what German folklorists used to call Schwundstufe: the dialogue between the two protagonists has been abandoned, the tasks - all from the second part of the original song - "have lost their dramatic function" (Bronson I, p. 10). There is no "cambric shirt", no "true love of mine" and no list of herbs. Instead a different set of plants has been turned into a nonsense rhyme. It is not clear how old this "new" type was at that time. Already in the 1820s peasant poet and collector John Clare from Northamptonshire knew this song (see Deacon, p. 21). Interestingly another even more simplified variant of this type was published same year in the magazine Notes & Queries (Vol. 7, No. 166, January 1, 1853, p. 8; also Child I, 2L, p. 20):

My father gave me an acre of land,

Sing ivy, sing ivy.

My father gave me an acre of land.

Sing green bush, holly and ivy.

I plough'd it with a ram's horn.

Sing Ivy, &c.

I harrow'd it with a bramble,

Sing Ivy, &c.

I sow'd it with a pepper corn.

Sing Ivy, &c.

I reap'd it with my penknife.

Sing Ivy, &c.

I carried it to the mill upon the cat's back.

Sing Ivy, &c.

[Then follows some more which I forget but I think it ends thus:]

I made a cake for all the king's men.

Sing ivy, sing ivy.

I made a cake for all the king's men.

Sing green bush, holly and ivy.

24 years later the next piece of information about this song family appeared in print, this time in the London magazine Athenaeum. On February 9, 1867 (p. 198, available at BPC) a correspondent who identified himself as "The Collector Of 'Popular Romances Of England'" - i. e. Robert Hunt, who had published a book with this title in 1865 - quoted this variant:

Can you make me a cambrick shirt,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Without any seam or needle work?

And I will be a true lover of thine.

Can you wash it in yonder well,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Where never sprung water nor rain never fell?

And I will be a true lover of thine.

Can you dry it on yonder thorn,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

Which never bore blossom since Adam was born?

And I will be a true lover of thine.

Now you have asked me questions three,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme,

As many wonders I'll tell to thee

If thou wilt be a true lover of mine.

A handless man a letter did write,

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme;

And he who read it had lost his sight,

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

He claimed that he had received this text from a "lady from Cornwall" who herself had heard it "when a child" from an "old woman of St. Ives, - a district beyond railways, - around which still linger many of the old-world customs, and much of the lore which was the stock-in-trade of the Cornish droll-teller". This is hard to believe. While the first four verses are more or less like those in "The Cambric Shirt" from Gammer Gurton's Garland the last one about the "handless man" clearly doesn't belong in this context. In fact it was first used only in 1843 by George Henry Borrow in his book The Bible in Spain (Vol. 2, p. 312, here at Google Books) and there is no evidence that it ever was traditional in England. How it came to be appended to this fragment of "Cambric Shirt" is not known. This was also noted by another correspondent, a Mr. Lonsdale, who sent in what he called the "original verses [...] the true version [...], as received in this country, to my knowledge, upwards of forty years": They were printed two weeks later (February, 23,1867, p. 262):

Canst thou make me a cambric shirt,

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

Without e'er a seam, or one stitch of work?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Canst thou wash it in yonder well,

Savoury, sage,rosemary, and thyme.

Where water ne'er rose, or rain ever fell?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Canst thou dry it on yonder thorn,

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

That never bore blossom since Adam was born?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Now thou hast asked me questions Three,

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

And I will do the same of thee.

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Canst thou find me an acre of land

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

Between the sea and the sea sand?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Canst thou plough it with a cow's horn,

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

And sow it all over with one peppercorn?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Canst thou mow it with a sickle of leather,

Savoury, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

And bind it up with a peacock's feather?

And, then, thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Unfortunately Mr. Lonsdale didn't tell his readers where exactly he had heard this variant. But it is very close to the text from Gammer Gurton's Garland. There are some minor variations, the refrain is only slightly changed - "savoury" instead of "parsley" - and the last verse is missing.

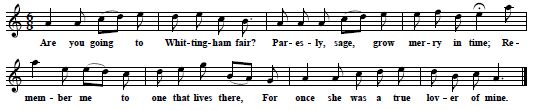

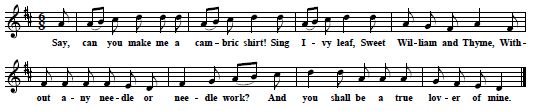

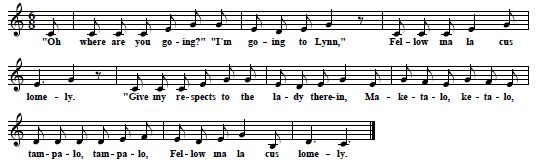

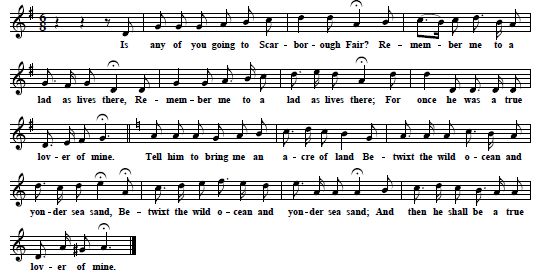

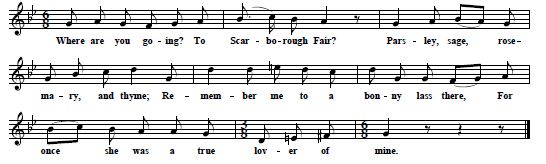

More important for a better understanding of this song family's history and development is a variant called "Whittingham Fair" that was first published in the Newcastle Courant on August 29, 1879 (BNCN, Gale Document Nr. Y3205322708) as part of a series called Northumberland Pipe And Ballad Music:

![5. "Whittingham Fair", tune & text from [John Stokoe], Northumberland Pipe And Ballad Music: Whittingham Fair, in Newcastle Courant,August 29, 1879 (BNCN, Gale Document Nr. Y3205322708); also in Stokoe & Bruce, Northumbrian Minstrelsy, 1882, p. 79-80. 5. "Whittingham Fair", tune & text from [John Stokoe], Northumberland Pipe And Ballad Music: Whittingham Fair, in Newcastle Courant,August 29, 1879 (BNCN, Gale Document Nr. Y3205322708); also in Stokoe & Bruce, Northumbrian Minstrelsy, 1882, p. 79-80.](../assets/images/WhittinghamFair-tune.jpg) |

Are you going to Whittingham fair?

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Remember me to one who lives there,

For once she was a true lover of mine.

Tell her to make me a cambric shirt,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Without any seam or needlework,

Then she will be a true lover of mine.

Tell her to wash it in yonder well,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Where never spring water nor rain ever fell,

Then she will be a true lover of mine.

Tell her to dry it on yonder thorn,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Which never bore blossom since Adam was born,

Then she will be a true lover of mine.

Now he has asked me questions three,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

I hope he'll answer as many for me,

Before he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to find me an acre of land,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Betwixt the salt water and the sea sand,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to plough it with a ram’s horn,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

And sow it all over with one peppercorn,

And he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to reap it with a sickle of leather,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme,

And bind it up with a peacock’s feather,

And he shall be a true lover of mine.

And when he has done and finished his work,

Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme.

Oh, tell him to come and he'll have his shirt,

And he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tune and text were reprinted three years later in Northumbrian Minstrelsy. A Collection Of The Ballads, Melodies, And Small-Pipe Tunes Of Northumbria (Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1882, p. 79/80), an interesting and important publication compiled by the Rev. J. Collingwood Bruce and John Stokoe. Here for some reason the last line of every verse was always: "For once she was a true love of mine". This was the very first time that an authentic tune for a song belonging to this family was published. The author of the article in the Newcastle Courant - it seems that it was Mr. Stokoe (see Rutherford, p.272) - noted that they "have heard it sung to different tunes, but prefer" this one which "has the clearest claim to be considered the original air, and is always sung to it in north and west Northumberland". The introductory verse is nearly identical to the one we know from the modern "Scarborough Fair" except that here the town's name is "Whittington".

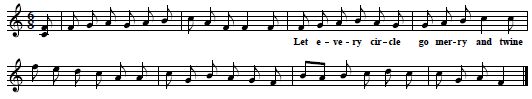

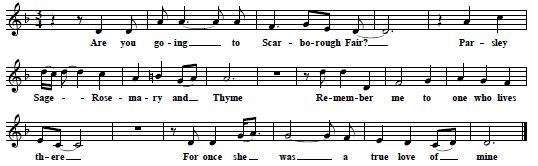

Interestingly this text is very similar to "Cambrick Shirt" from Gammer Gurton's Garland. It looks as if someone had taken the version from the book, added the introductory verse with the messenger and then changed the beginnings of the first lines of every stanza from "can you" to "tell him/her". But the whole text is much too "clean" and an editor's hand is clearly discernible. Thankfully in this case the original version is available. According to the newspaper article the "tune and the ballad" were contributed "to the Antiquarian Society's collection about twenty years ago" by Mr. Thomas Heppell [sic!] of Kirkwhelpington. In 1855 the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne - an organization founded in 1813 - "appointed a committee 'to protect and preserve the ancient melodies of Northumberland'". Two years later the Duke of Northumberland offered prizes for the two best collections of "ancient Northumbrian music". Thomas Hepple from Kirkwhelpington, a "local singer", sent in his manuscript of 24 songs, in his own words "some old ballads I have had off by ear since boyhood" (Lloyd, Foreword to Bruce/Stokoe, pp. vi, xi; Rutherford 1964, pp. 270-2). "Whittingham Fair" was one of the pieces included (Thomas Hepple manuscript, now available at FARNE). The tune was the same. It only was transposed for publication from am to em, a fifth lower. But the text looks a little bit different:

|

Are you going to Whittingham fair,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

Remember me to one that lives there,

For once she was a true lover of mine.

Tell her to make me a cambric shirt,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

Without even a seam or needle work,

Then she shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell her to wash it in yonder well,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

Where it never sprung where never rain fell,

Then she shall be a true lover of mine.

Three hard questions he's putten to me

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

But I'll match him with other three,

Before he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to buy me an acre of land,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

Between the sea and the sea sand,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to plow it with a hunting horn,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

And sow it with the [?] corn,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to sheer it with the hunting leather,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

And bind it up in a pea-cock feather,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine.

Tell him to thrash it on yonder wall,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

And never let one corn of it fall,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine..

After he has ended his work,

Parsley sage grow merry in time,

Go tell him to come and to have his shirt,

Then he shall be a true lover of mine.

This is a much more authentic text. It sounds a little uneven at times as if Mr. Hepple had some problems remembering the original words. At least one verse is missing, the one with the third task for the girl. The penultimate verse - "thrash it on yonder wall" - can't be found in any other earlier variant and it was deleted by the editor of the text published in the newspaper and in the book. But for some reason it was reinstated when Rokoe published this song again in an article in the Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend in 1889 (p. 7).

This additional verse suggests that Mr. Hepple's text represents a different line of tradition. His version also includes elements of both of the ideal-typical subtypes I have proposed: the messenger in the first verse is known from IIa while the "cambric shirt" has been part of IIb. Interestingly the second part doesn't start with the girl sending the messenger back to the man as in IIa. Instead there is a variant form of the verse common to the two published versions and the subtype IIb: here she states that she has received three questions from him and then announces that she will give him the same amount. The refrain in the second line is a mixture of those known from these two subtypes: in the first half there are two herbs, parsley and sage, while the phrase "grow merry in time" is known from earlier variants.

I don't know who has rewritten Mr. Hepple's text. I presume it was either Mr. Stokoe or the Rev. Bruce. But whoever it was he did his best to "correct" the lyrics with the help of "Cambrick Shirt" from Gammer Gurton's Garland. He not only deleted the additional verse but also added the one that was missing. Besides that every verse got its "right" shape and not at least the refrain with the complete list of herbs - "parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme" - replaced the seemingly corrupt form used by Mr. Hepple. The editors wanted to save these kind of songs from oblivion, they wanted the people to sing them again. In this respect it was not a bad idea to add a more coherent text that corrects the unevenness of the original words. But on the other hand these kind of "corrections" can be severely misleading because the use of parts from other variants obscures the real background and provenience of the text in question. As noted above this was for example also the case when Kinloch supplemented the text he had collected from oral tradition with some stanzas from the old black-letter broadside.

In fact "Whittingham Fair" as published in the Newcastle Courant and in the Northumbrian Minstrelsy is a folklorist's ballad, a kind of "booklore" that later started a life of its own and a new line of tradition. The edited text became a reference point for subsequent collectors and scholars who then - as will be seen - used it as model to "correct" and "improve" other "imperfect" or fragmentary variants unearthed from oral tradition. It was even included by Professor Child in his English and Scottish Popular Ballads (II, pp. 495-6). Apparently nobody told him about the original version in Mr. Hepple's manuscript.

The Northumbrian Minstrelsy was indeed an influential collection, according to Gregory (2010, p. 68) even a "foundational document of the Late Victorian folksong revival". But it also has drawn much criticism because of the editors' policies (see Gregory 2004, pp. 369-76 & 2010, pp. 68-84). But that's the way it was at that time. It is always a good idea to check the original sources. Much of what was published has been tinkered with and shouldn't be used uncritically. But of course this applies to all collections of so-called "folk-songs".

Sadly Mr. Hepple's manuscript has been neglected both by Stokoe and Bruce who only used very few of his songs for their book and also by later scholars who - as far as I know - have ignored it. Thomas Hepple must have been a very educated man: he could not only read and write but was also familiar with musical notation. Maybe that was the problem. Many folk song scholars preferred the products of illiterate peasants. But his collection is an excellent resource and a useful historical document because it shows what kind of songs were popular in Northumberland at that time. Some of this pieces are derived from printed texts, for example "Down In Yon Meadows" (see this page at FARNE). This is a slightly abbreviated variant of the "Unfortunate Swain", an immensely popular broadside ballad. In case of "Whittingham Fair" it is not clear how much it owes to the commercially published versions of songs from this family. But with one verse not known from either "Humours of Love" or "Cambrick Shirt" it seems to represent at least partly an otherwise undocumented line of tradition.

VII.

1882 not only saw the publication of the Northumbrian Minstrelsy. A much more important and influential work also found it way to the printer: the first part of the first volume of the English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Professor Child from Boston was finally presented to the public after many years of research. But this massive collection was of course intended for a more academically inclined readership. The song family discussed here found itself canonized as No. 2 with the title "The Elfin Knight". Child wrote a groundbreaking and masterful scholarly account of this group's history that is unsurpassed to this day although it surely needs some critical adjustments. But he also published a great number of variants he had found in books and manuscripts. In some way this new standard work symbolized the end of an era. It was first and foremost an appraisal and an inventory of all what was known about historical ballads at that time. But it also can be seen as the start of a new era because henceforth Professor Child's canon served as a kind of roadmap for all future researchers and collectors.

Since the 1880s more variants of songs from this family came to light. In 1887 Walter Rye, antiquary from Norfolk, wrote an article for the magazine East Anglian (p. 211-213) where he published two ballads "taken down nearly half a century ago [...] ca. 1840". Even the name of the singer is given. It was "Sam. Self, of Hethersett", a village in Norfolk, some miles from Norwich. The second one was "Cambric Shirt":

I pray you to make me one Cambridge Shat [sic!],

Savory sage, rosemary and thyme

Without ather niddle, nor yet niddle work

And then you shall be a true lovyer of mine.

And wash it all over in a dry well,

Savory sage, rosemary and thyme

Where niver was water, nor niver rain fell

And then you shall be a true lovyer of mine.

I pray you to hang it all on a thorn

Savory sage, rosemary and thyme

Where niver was bud since man was born

And then you shall be a true lovyer of mine.

I pray you to hire me one acre of land

Savory sage, rosemary and thyme

And crop it all over with one pupper corn

And then you shall be a true lovyer of mine.

And pick it all up with a cobbler's awl

Savory sage, rosemary and thyme

And stow it all into a mousen's hall

And then you shall be a true luvyer of mine.

This is of course only a fragment of six verses. Most interesting is the rhyme mousen's hall/Cobbler's awl in the last verse. It can be found both in the "Humours of Love", the broadside published in the 1780s and in the the Scottish version sent to the Scots Magazine by Mr. Ignotus in 1807. But it seems that Mr. Self's variant is a fragmentary relic of the broadside because the wording of all the other verses can easily be traced back to that particular text. Even more interesting is that the name of the tune is given here: "Robin Cook's Wife". I must admit that I have never heard of one with that name. But in fact the other song published in the article, "The Old Grey Mare", starts with exactly this phrase:

Robin Cook's wife she had a grey mere

Hum hum - hum hum hum hum

If you had but ha' seen her, O lauk how you'd stare

Singing faldedal fiddlededal, hy dum dum.

[...]

It has exactly the same structure as "Cambric Shirt": four lines with internal refrains in the second and fourth. One may assume that Mr. Self used to sing both songs to the same tune. But unfortunately this particular melody has never been found. Bronson (I, p. 9) claims that "The Old Grey Mare" is "alternatively known as 'Roger the Miller' and 'Beautiful Kate'". But that is a completely different song that has nothing to do with this "grey mere". Nonetheless this is an interesting variant not only because it suggests that copies of the broadside had made it to Norfolk. But it is also an example of how the song can disintegrate. It is no longer recognizable as a dialogue between the two protagonists because the start of the girl's reply is missing. What has remained is only a series of impossible tasks á la "Acre of Land".

Since the 1880s also a new generation of song collectors came to the fore in Britain, at first people like the Rev. Baring-Gould from Devon and Frank Kidson from Leeds and after the turn of the century for example Cecil Sharp, Ralph Vaughan Williams, H. E. D. Hammond and, from Scotland, Gavin Greig and the Rev. Duncan. Especially the years 1903 - 1913 became "the golden age of English and Scottish folk song collecting" (Gammon, p. 15). Thankfully these collectors have also noted many tunes as they were interested in the songs and not only in texts like most of the old ballad scholars.

The term "folk song" was a new invention. It "came into fairly general use only in the 1890s" (Gregory 2010, p. 27). I don't want to discuss the ideology of this movement nor the ideological struggles of today's folk song scholars (but see Bearman 2001 and Gregory 2010). I must admit that I have really learned to admire these collectors' accomplishments and the great body of songs they have assembled. They were on a rescue mission, they wanted to save this kind of songs from oblivion. Baring-Gould was amongst those who sounded the alarm and claimed in the Introduction to his Songs and Ballads of the West (p. ix) that "in five year's time all will be gone; and this is the supreme moment at which such a collection can be made".

On the other hand I am still astonished about the recklessness - or naivité - with which they took into their possession other people's music. In the early volumes of the Journal of the Folk-Song Society it is pointed out that "all versions of songs and words published in this Journal are the copyright of the contributor supplying them" (see f. ex. Vol.II, N. 8, 1906, title page). This attitude suggests that - notwithstanding the often good relationship the collectors had with their informants - they somehow still regarded them not as individual artists but as members of an anonymous "folk" that has only preserved the songs they were looking for.

But at first it must be noted that what they collected was far from being representative. "The country lanes were not full of collectors on bicycles", they were a very small minority that "did no more than scratch the surface of a rich vernacular musical culture which they only partially documented" (Gammon, p. 15). Besides that they had a very limited perspective. The song collectors were only interested in particular genres, they were very selective and had a deplorable bias against contemporary popular music. In fact they preferred to look out for relics of "old songs". Their favorite informants were illiterate old people in remote rural areas although in practice the singers were not always as illiterate and old as they wanted their readers to believe (see Graebe 2004, p. 178 about Baring-Gould; Bearman 2000 about Sharp).

The folk song collectors were mostly very critical of the role of commercially published broadsides. Baring-Gould once wrote to Professor Child that he regarded them only as "bad representations of the original" because the "printers got hold of them in town". According to this ideology "the purest forms were preserved" in the country (quoted in Atkinson 1996, p. 41). Of course some collectors - like Kidson and Lucy Broadwood - "embraced a wider range of vernacular songs" (Gregory 2010, p. 27) and were somehow less doctrinaire than Baring-Gould or Cecil Sharp. But even the latter took the chance and collected in urban areas "if the material was there" (Bearman 2001, p.130).

It should be clear that the products of the folk song collectors can not be used uncritically. There are at least three important "filters" that have to be taken into account. First, many of the informants were in fact old people who had learned the songs in their youth, sometimes from parents or grandparents. What did they forget, how did the song change in the course of several decades? This is of course hard, not to say impossible to figure out. Often only a fragmentary relic has survived.

Equally important but also impossible to trace is the relationship between what the informant knew of a song, what he sang to the collector and what was then written down by the latter. Some Folklorists for example were more interested in tunes than in texts and they only noted one verse or maybe only those they hadn't heard from former informants. What was the collectors' input? Did they help out a little bit when the singers had forgotten something?

In 1952 an American song collector took down a version of our song from an informant who used as the refrain of the second line the phrase "Rosemary one time". The professional folklorist was of course familiar with many other variants of this song and he "suggested 'rosemary and thyme'". In this case the singer "rejected" this proposal and "insisted" on his own text as he had learned it (see Owens, p. 4). But this makes me wonder how often song collectors have managed to insert corrections of this kind into a song that was then passed on as the sole work of the informant. This may sound like nitpicking but it only goes to show that of course even archival sources - directly from the notebooks of the collectors - are not without its problems.

Even more problematic are of course published collections of "folk songs", especially those directed at an non-academic audience. In these kind of books the songs have nearly always been edited, sometimes more and sometimes less. It is not my point to accuse the publishers of producing "inauthentic" songs. In fact they all did what they thought they had to do. Their major aim was surely to revitalize these old songs and bring them back to the people, not primarily the poor folks from whom they had secured this treasure trove but the educated middle classes.

Much of what had been collected was not usable for such a purpose. Many texts were incomplete or only fragmentary relics and some of them were not up the the moral standards of the day. But these kind of song collections "were obliged to provide full, singable, intelligible, and grammatically-correct texts which conformed to the decencies of the time" (Bearman 2001, p. 163). So the collectors and editors did their best to repair and "improve" the texts by collating parts from different variants, they combined tunes and words from different sources and sometimes they even wrote or composed something themselves.

In fact all published versions have to be regarded as very suspicious. Often they had not much to do with what the real "folk" sang and remembered. Even small emendations or "corrections" can be misleading. Academic editions should be more reliable and and more closer to the original texts. On the other hand these collections of "folk songs" were immensely influential for the further history and development of those songs. As already noted many collectors were critical of the commercially published broadsides. But in fact they created a new industry of printed "folk songs" that became the starting point for a new canon. The folklorists have given these old songs a new life, but on their own terms.

VII.

In his article in the Newcastle Courant in 1879 John Stokoe had noted that the song discussed here was known both with and without introductory verse and wondered "if the decapitated version [was] the correct one or not". I won't discuss this here anymore as I have offered my speculations in a previous chapter. Instead I will present what the English, Scottish and Irish collectors have found and published, first the versions without a storyline - á la "Cambrick Shirt" and "Humours of Love" - and then those with an introductory stanza.

The first one to mention here is the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924; see the biographical overview by Martin Graebe on Songs of the West; also Graebe 2004; Gregory 2010, pp. 147-196). He was one of the outstanding men of letters of his time and his productivity as a writer was astounding. Besides countless articles he authored "more than 160" books (Graebe 2004, p.175), among them novels, collections of sermons and historiographical literature like The Lives of the Saints in 16 volumes, The Book of Were-Wolves, Germany, Present and Past, Curious Myths of the Middle Ages, Historic Oddities and Strange Events, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, Family Names and their Stories, The Tragedy of the Caesars and A Book of the Pyrenees, to name just a few (many are now available online at the Internet Archive).

In 1881 Baring-Gould became parson and squire in a parish in West Devon and in the late 1880s he started to collect "old songs", the kind of songs he fondly remembered from his youth:

"When I was a boy I was wont to ride round and on Dartmoor, and put up at little village taverns. There - should I be on a payday - I was sure to hear one or two men sing, and sing on hour after hour, one song following another with little intermission. But then I paid little attention to these songs. In 1888 it occurred to me that it would be well to make a collection - at all events to examine into the literary and musical value of these songs, and their melodies" (Introduction to Songs and Ballads of the West, p. vii; see also Graebe 2004, p. 175).

He received some texts from correspondents but he also went out himself on collecting expeditions where he was often accompanied by either Henry Fleetwood Sheppard or F.W.Bussell, both also clergymen. They were much more experienced musicians than Baring-Gould and wrote down the tunes for him.

Between 1889 and 1891 his first collection of songs was published in four parts. He called it Songs and Ballads of the West (available at the Internet Archive). According to the subtitle this was a "collection made from the mouths of the people". But in fact it was a very problematic work. Many of the texts and tunes were heavily edited, sometimes he even wrote something himself. He has been harshly criticized for his editorial practices but "unlike some of his contemporaries, he freely admitted to heavy bowdlerization, and to rewriting of whole texts, as well as marrying words and tunes from different sources" (Graebe 2004, p. 176). And in his eyes this was of course a completely legitimate approach.

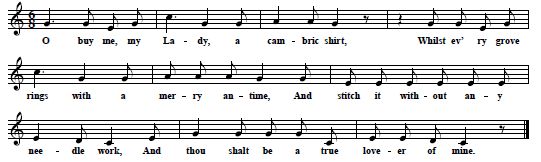

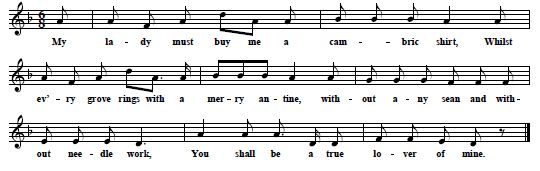

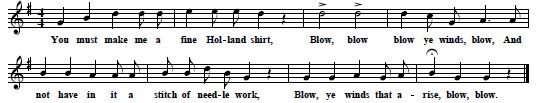

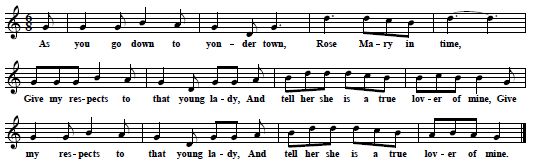

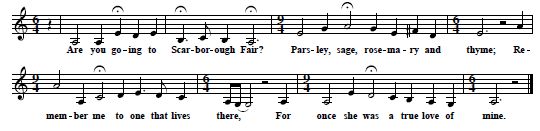

In 1905 a new edition of this collection was published, this time under the musical editorship of Cecil Sharp. It seems that here the songs were all a little more closer to the "mouths of the people". Perhaps Sharp took care that Baring-Gould didn't go too far. There is no version of the song discussed here in the first edition. But in 1905 he included a variant with the title "The Lover's Task" (No. 48, pp. 96-7; notes, p. 14-16; tune also in Bronson I, 2.33, p. 23):

|

[He:]

O buy me, my lady, a cambric shirt,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

And stitch it without any needle work,

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

O thou must wash it in yonder well,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.´

Where never a drop of water in fell,

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

And thou must bleach it on yonder grass,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

Where never a foot or hoof did pass.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

And thou must hang it upon a white thorn,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

That never blossom'd since Adam was born.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

And when that these works are finished and done,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

I'll take and marry thee under the sun.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

[She:]

Thou must buy for me an acre of land,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

Between the salt sea and the yellow sand.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Thou must plough it o'er with a horses horn,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

And sow it over with a peppercorn.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Thou must reap it, too, with a piece of leather,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

And bind it all up with a peacock's feather.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

Thou must take it up in a bottomless sack,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

And bear it to the mill on a butterfly's back.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.

And when these works are finished and done,

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

I'll take and marry thee under the sun.

And thou shalt be a true lover of mine.