|

The "Guittar" In Britain

1753 - 1800

Introduction

I. The Guittar In Britain 1753 - 1763

II. The Next Fifty Years

III. Music For The "Guittar" Published In Britain 1756 - 1763 - A Bibliography

IV. Some Biographical Sketches

List Of Databases And Literature

Postscript 2.2.2014 new

This text is also available - in a more academic form with all the notes at the bottom of the pages - for download as a pdf-file.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

During the 1750s an instrument commonly called the "guittar" became immensely popular in Britain. This was not a guitar as we know it today but a close relative of the cittern:

"Although the guittar came in a variety of designs, most of the surviving examples share the following features: a pear-shaped body with a flat back and a string-length of 42cm; six courses of metal strings, the bottom two being single-strung and the upper four in unison pairs; watch-key tuning, which replaced peg tuning; twelve chromatically placed brass frets; and as a means of transposing song accompaniments, holes drilled through the fingerboard between the first four frets, through which a capo tasto could be fixed" (Coggin 1987, p. 205; see also Armstrong 1908, pp. 5-24, Walsh 1987 and the interesting video by David Kirkpatrick at YouTube).

In the decades before the 1750s plucked string instruments had been totally out of fashion. Only since 1756 a n immense flood of books containing music for the "guittar" was published in England and Scotland and it remained in use for more fifty years. During the early years of the 19th century this instrument fell into obscurity and was then replaced by the new six-stringed Spanish guitar. n immense flood of books containing music for the "guittar" was published in England and Scotland and it remained in use for more fifty years. During the early years of the 19th century this instrument fell into obscurity and was then replaced by the new six-stringed Spanish guitar.

The following text in attempt at a history of this instrument. Much of the information used here is taken from contemporary newspaper adverts which were immensely helpful, especially those from the 17th - 18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers. Throughout this work I use the term "guittar", with two "tt"-s, that was common for most of the time. "Guitar" with one "t" also occurred regularly but not so often. The term "English guit(t)ar" came into use only late in the18th century, mostly to distinguish it from the Spanish guitar. The guittar was of course also quite popular in North America (see Rossi 2001) but I had to leave that out and limit myself to the development in Britain.

In the first part I will deal with the instrument's introduction in 1753 and its history until the early '60s. The major protagonists were the actress Maria Macklin who was the first one to play it on stage, Mr. Thomas Call, the first known teacher of the guittar and instrument maker Frederick Hintz who may have been its inventor. Additionally there is a brief overview of the guittar literature published between 1756 and 1763. The second part includes a short account of the history of the guittar until the end of the century as well as chapters about the so-called "Piano Forte Guittar" and about the music teacher and instrument maker Edward Light. Part III is an extensive bibliography of the guittar literature published until 1763 while Part IV offers some biographical sketches of musicians who have written music for this instrument.

I. The Guittar In Britain 1753 - 1763

1. Miss Macklin And Her Pandola

"The guitar became all the rage in consequence of Miss Macklin having played on that instrument in 'The Chances'. Advertisements accordingly appeared, offering to give instruction on 'the Citter, otherwise Guittar, otherwise Lute or Pandola'" (James Hutton 1857, p. 318).

In fact young actress Maria Macklin (c. 1733-1781; see BDA 10, pp. 33-37), daughter of Charles Macklin, played this instrument first in 1753 in The Englishman in Paris, a "Comedy of Two Acts" by Samuel Foote. Playwright Foote had been in Paris. There he had witnessed "the ridiculous behaviour of his country-folk in France and their absurd attempts at aping foreign ways and habits" and so he wrote this farce. Charles Macklin had taken great care to give his daughter the best possible education and this was her first major role. The part of "Lucinda" was created especially for Miss Macklin so she could show her abilities as a singer, dancer and instrumentalist. (see Fitzgerald 1910, p. 105, Cook 1805, pp. 66-7, Appleton 1960, p. 96).

The successful premiere of The Englishman in Paris took place on March 24, 1753 at Covent Garden (Public Advertiser, March 24, 1753, GDN Z2001065056, BBCN; London Stage 4.1, p. 360). The play was well received and Miss Macklin's performance captivated the audience. Francis Delaval noted in a letter to his brother John:

"I just come home from Mr. Foote's farce, which went off with applause. Miss Macklin danced a minuet, played on the 'pandola', and accompanied it with an Italian song, all which she performed with much elegance" (Delaval Manuscripts, p. 201, Appleton 1960, p.96).

In fall that year the Macklins joined David Garrick's company and Foote's play was then performed regularly and with great success at Drury Lane during the next seasons (see London Stage 4.1, p. 385, BDA 10, p.33). The following year Garrick also revised The Chances, an old piece by Sir John Fletcher. The premiere was on November 7, 1754 and the actors were "Dress'd after the Old Italian and Spanish Manner" (London Stage 4.1, p. 450, Public Advertiser, November 7, 1754, GDN Z2001068639, BBCN). Miss Macklin played the role of the "First Constantia" and was allowed to repeat her performance on the pandola.

Why was the guittar at this time called the "pandola"? In fact the pandola was another fashionable exotic instrument that had been introduced in England by one Nicolas Cloes some years earlier . Nothing is known about Mr. Cloes. He most likely was a traveling performer from the continent, perhaps from Germany, France or the Low Countries, who only came to Britain every few years. In the late '40s he compiled a book of One Hundred French Songs Set for a Voice, German Flute, Harpsichord and Pandola for publisher John Walsh (see the first advert: General Advertiser, January 4, 1749, GDN Z2000419104, BBCN; see also Smith/Humphries, Walsh, p. 85-6, Nos. 382 & 383 and Copac) and dedicated it to "Their Royal Highness The Prince and Princess of Wales". This was the only book ever published for the "pandola" but there were no special arrangements, the music only "consists of just a treble clef vocal line and a figured bass for the harpsichord. The other instruments are alternatives to the voice" (Tyler/Sparks, p. 30).

For the next couple of years nothing was heard of him but on March 22, 1753 - two days before the premiere of The Englishman In Paris - a "Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Musick" took place in London. This was a benefit show for Mr. Cloes, who - according to the advert - "will accompany with the Pandola the chief Airs" (see Public Advertiser, March 19, 1753, GDN Z2001065030, BBCN). In December 1754 he was with his wife and son in Dublin for another benefit, a "Comic Concert. Vocal Parts by Signor, Signora and Master Cloes [...] Signor Cloes will accompany the Songs with a new Instrument, called the Pandola". But from the advert in the Dublin Journal we also learn that he was "Musician to H.R.H, the late Prince of Wales [...] "who had the Honour of teaching the Princess of Wales the Instrument, called, the Pandola" (quoted from Boydell, DMC, p. 203).

Then he vanished once again only to reappear nearly eight years later when he placed a message "To the Lovers of the Pandola or Guittar" in the Public Advertiser on January 12, 1762 (GDN Z2001083608, BBCN):

"Mr. Cloes having been intreated by many of the Nobility, Gentry, and others to return to England, on order to give his Instructions on the Pandola, gives the Public this Notice, that he may be spoken with at Mr. Lombardi's, Operator for the Teeth, in the Haymarket, near St. James's. N. B. The Guittar or Citron being an Instrument that has been found very deficient in many Cafes, especially in regard to its being confined to one key only, as well as that it has not answered the first design, which was that of accompanying the Voice, has made several Persons lay it aside, and has taken to the Pandola. It is an Instrument far superior to the Guittar, on account of its playing in several Keys, and accompanies the Voice most agreeably. This instrument is taught in the same Manner, and with the same Ease, Grace, and Expedition, as the Guittar".

But at this point he was much too late and had no more chance to promote his instrument because in the meantime the guittar had become so immensely popular. Since then Mr. Cloes was never seen or heard of again. It should be clear that the pandola was not a guittar. Miss Macklin - or whoever was responsible - only borrowed that name for her new instrument. The term "pandola" was then quickly forgotten and later never used again.

When in October 1759 The Englishman In Paris was first staged in Dublin an otherwise unknown Miss Rosco played the role of "Lucinda, with the Song, Guitar and Minuet" (Boydell, DMC p. 252). In 1761 the play was performed again at Drury Lane and in the advert it was announced that "Miss Macklin will sing a song and accompany herself on the Guittar" (Public Advertiser, April 17, 1761, GDN Z2001081561, BBCN).

By all accounts Maria Macklin was the first to play a guittar on stage. Her performances since March 1753 first at Covent Garden and then at Drury Lane helped to popularize this instrument and her name remained connected to the guittar. As late as 1768 she played it once again. Another revival of Foote's farce at a benefit for Irish actor Robert Mahon included "a Minuet and Duetto, accompanied with two Guitars, by Miss Macklin and Mr. Mahoon [sic!]" (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, April 26, 1768, GDN Z2000360906, BBCN).

2. Thomas Call And Other Early Guittar Teachers

The first one to offer lessons for the guittar was one Thomas Call in London in 1754. His earliest advert appeared on March 2, 1754 in the Public Advertiser (GDN Z2001067114, also Public Advertiser, May 15, 1754, GDN Z2001067557, BBCN):

"Ladies or Gentlemen desirous to learn to play on the Citter, otherwise Guittar, may hear of a Person who teaches the instrument [...] This instrument differs nothing from the Mandalien [sic!], unless in Tuning; easier to play, and yet more copious, having two Strings more than the Mandalien. It's a very proper instrument [...] especially to such Ladies as find the harpsichord too difficult for them, it being a pleasant melodious Musick, adapted to the Voice and delightful to sing with [...]".

Being a music teacher was a hard job at that time. They didn't earn much and were always looking for new clientèle among the upper classes, those who could afford to pay private teachers (see Leppert 1985). But many of their students were not necessarily musically gifted. Mr. Call was here clearly testing the market and tried to promote this new instrument by emphasizing its advantages and comparing it to the "mandalien" that was obviously a little better known at that time. His target group were the amateurs looking for an easy instrument to play and to sing with, not at least those who found "the harpsichord too difficult for them". Though the guittar was later played mostly by women his advert was still directed at "Ladies or Gentlemen". A new advert appeared some months later in the Whitehall Evening Post or London Intelligencer, August 1, 1754 - August 3, 1754 (Z2001652088, BBCN):

"As the Instrument call'd the Citter, otherwise guittar, becomes so universally approved by those Ladies and Gentlemen, that have learn'd it, as being so engaging for private Amusement, so easy to sing with, and so soon learn'd, make many Ladies and Gentlemen desirous also of learning the same [...] This Instrument is much of the Nature of the Pandole, or Mandaleine, but by it's being otherwise tun'd, and having two Strings more than the Pandole, makes it have a greater Compass, and much easier to play."

Most interesting here is the comparison to the "Pandole". But I think Mr. Cloes would have surely disagreed with the claim that the guittar had "a greater Compass" than his own pandola. Strangely this teacher didn't mention his name in his two first two adverts. But from the next one published on April 8, 1755 in the Public Advertiser we learn that he was Mr. Call, "Teacher of the Citter, otherwise guittar, otherwise Pandola":

"[...] he having had the Honour of teaching many Ladies and Gentlemen of Rank, and also Miss Macklin, this being the Instrument which she plays in the Chances, and in the Englishman in Paris. As it is so universally approved by those who have learnt it or heard it, it would be needless to say any more of it than this, that it is portable, soothing, and pleasant; and it can be tuned several different Ways, I teach it either in Italian, Spanish, or German Manner." (GDN Z200106958, BBCN)

It seems that at that time different tunings for the guittar were common, although later it was usually played mostly in "C". Interestingly here he claimed for the very first time that he had taught Maria Macklin to play that instrument. At that time both The Englishman in Paris and The Chances were still performed at Drury Lane (see f. ex. Public Advertiser, February 4, 1755, GDN Z2001069184 and April 7, 1755, GDN Z2001069579, BBCN). It is surely possible that Thomas Call had been one of the teachers hired by Macklin, sen. to educate his daughter. It is only a little bit surprising that he didn't refer to her in his first two adverts.

Since then he advertised regularly and never forgot to note that the guittar was "the very identical Instrument which is play'd on in the Chances and in the Englishman in Paris" and that he "is the only Person who has, and still continues to each Miss Macklin, this and other Particulars relating the Grounds of Musick" (see Public Advertiser, September 24, 1755, GDN Z2001070603, BBCN). But the competition was close and other teacher were also offering their services with adverts, like a Mr. Alexander in the Public Advertiser on December 30, 1755 (GDN Z2001071178, BBCN):

"Any Noblemen, Ladies, Gentlemen, or others, that are desirous to learn to play on the Instrument upon which Miss Macklin plays on the Stage, may be instructed therein in an elegant, concise, musical Manner by a proper Master of upwards of thirty Years of Experience on the said instrument. He has had the honour to teach several of the Nobility and entry, who after trying other Masters, have declared that his Method both of teaching and playing, was much superior to any of the others [...]".

He also referred to Miss Macklin but didn't claim to be her teacher. Thomas Call reacted quickly and placed another ad in the Public Advertiser on January 12, 1756 (GDN Z2001071236, BBCN):

"To the Nobility and Gentry in general that are desirous to learn the Citter, or Guittar, otherwise Lute or Pandola [...] Mr. Call begs Leave to inform them that he has a peculiar Method of teaching the fingering Part of this Instrument, different from any other Teacher that has yet appeared in public, whereby the more difficult Parts of Music can with more Ease and Quickness be performed that what has hitherto been taught by others. Such Ladies as are inclined to learn it, may be taught both by Musical Notes and Tablature in so demonstrative a Manner as not to be subject of Errors; and can in short Time furnish them with the true Knowledge and Ground of this Instrument, as being sufficiently acquainted with the Grounds of Music, and a teacher of the Harpsichord. Ladies who chuse the Use of he instrument for learning on, might be supplied with one at a very small expence [...]."

The next month he also announced that he "teaches this Instrument in a different and more authentic Plan than any other Teacher that has yet appeared in Public, and in six different ways of tuning". (Public Advertiser, February 28, 1756, GDN Z2001071446, BBCN). Nonetheless other music teachers took the chance and jumped on the bandwagon like for example the "Gentlewoman who has practised the Guittar for many years Abroad, teaches at present in the most compleat Manner and easiest Terms" (Public Advertiser, November 13, 1756, GDN Z2001072589, BBCN). I only wonder what kind of instrument this lady had played "for many years abroad". It can't have been this new guittar.

Musicians of all kinds were also forced to make themselves familiar with this instrument. "Professionals [...] had to be able to play any exotic instrument their aristocratic pupils wished to learn" (Holman 2010, p. 163). A typical example was violin virtuoso Giovanni Battista Marella. He had worked in Dublin as a conductor and instrumentalist between 1750 and 1754 and then moved to London. There is no evidence that he had used the guittar during his time in Ireland. He must have learned to play it shortly after he his arrival in England. It also seems that he was the first professional musician who played the guittar in a concert. His first documented performance with that instrument was in Oxford on December 2, 1756:

"For the Benefit of Mr. Orthman, On Thursday the Second of December will be performed in the Music Room, a Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Music; the Principal Violin by the celebrated Signior Marella; who, by particular Desire, will perform on the Viola d'Amour and Guittar" (Oxford Journal on November 27, 1756, p. 3, BNA).

The phrase "by particular Desire" suggests that he had played it in public already earlier. There is also good reason to assume that at that time he was working as a teacher for the guittar. Popular musicians like Marella didn't need to place adverts in newspapers, they were able to find their students in more informal ways.

The guittar quickly became popular all over England and Scotland. In 1758 young Charles Claggett (see Holman 2010, pp. 165-168) from Ireland was in Newcastle where he taught not only the violin and violoncello but also the "Guitar" and "Citra" (Southey 2004, p. 67). His brother Walter (1742-1798, see BDA 3, pp. 291-2) , "Musician and Dancing-Master", happened to be in Bath that year where he offered to instruct the "Ladies and Gentlemen" in "Dancing, And the use of the following Instruments, viz. The Violin,Violoncello, Guitar, German Flute, Likewise Tunes, Harpsichords,and Spinetts" (advert quoted by Leppert 1985, p. 140-1). Mr. Roche, a "Music Master" from Germany arrived in Aberdeen in 1758. Besides "the Fiddle, the German Flute, the Hautboy, Bassoon, Violoncello, French Horn, etc" he also taught "Singing and the Guittar" (Farmer 1947, p. 325).

Music publisher Robert Bremner from Edinburgh had sent his son to study guittar with famous composer and violinist Francesco Geminiani (see NG 4, p. 314) and in 1759 Bremner, jun. had "given up everything else to teach that instrument and had not an hour to spare this eleven months" (quoted by Coggin 1987, p. 209). Italian violin player Olivieri had arrived in London in 1756 but moved to Edinburgh two years later and settled here. In 1759 he also offered his services as a teacher for the guittar in an advert published by music shop owner Neil Stewart (see Public Advertiser, May 3, 1756, GDN Z2001071726, BBCN; Caledonian Mercury, January 31, 1758, February 25, 1758, November 14, 1759, BNA).

At this point all the "Ladies and Gentlemen" eager to learn the guittar could easily find a teacher. Many musicians found it necessary to include that instrument in their portfolio. Italian violinist and singer Guiseppe Passerini (see BDA 11, p. 233, McVeigh 1989, pp. 92-4) had been in England since 1752. Besides singing and playing on London and provincial stages he also worked as music teacher. In summer 1760 he announced that he planned to open "an Academy in the great Parlour of his House [...] to Lecture and Instruct young Ladies and Gentlemen in any of the following Branches of Musick: As Singing, Playing Lessons or Thorough Bass on the Harpsichord or Organ, the English and Spanish Guittar, the Violin, Viol d'Amour, Viola Angelica, Violoncello, &c. [...]" (London Chronicle, July 24, 1760-July 26, 1760, p.2, GDN Z2001672466, BBCN). This was to my knowledge the very first time this instrument was called the "English Guittar", a term clearly invented to distinguish it from the "Spanish Guittar". Passerini must have been one of the first teachers for the latter that was at that point barely known in England.

3. Frederick Hintz - "Guittar-maker to her Majesty and the Royal Family"

The first one to offer this new instrument in a newspaper advert was one Frederick Hintz. He had a shop "at the Golden Guittar, in Little Newport-Street" and announced that he "Makes and Sells all Sorts of Guittar in the best Manner". This ad can be found in the Whitehall Evening Post or London Intelligencer, August 1, 1754 - August 3, 1754 (GDN Z2001652088, BBCN). Interestingly it was placed directly under an advert by guittar teacher Thomas Call.

John Frederick Hintz (1711-1772, see Graf 2008 and Holman 2010, pp. 135-169) was a German craftsman who spent most of his life in England. He had started out as a furniture-maker with a store in London. But in 1737 he "became acquainted with the Moravians in London" and a year later he gave up his shop and left England for Germany "in order to [...] devote his life to the church" (Graf, p. 10). During his time in Germany Hintz must have learned to play the cittern that "was considered a 'divine' instrument among eighteenth-century Moravians" (Graf, p. 8). It played an important role in their "liturgical life", for example it was often used to accompany the singing of hymns and to "comfort the sick prior to death" (Graf, pp. 8, 26, 29, 32).

In 1747 he returned to England, at first to Fulneck and then 1749 again to London where he opened a new shop early in 1752. There he still sold furniture (Holman 2010, p. 143) but it seems that at that time he also knew how to build musical instruments. He had already made harpsichords for two congregations in the late 1740s and Holman (p. 147) suggests that he also "started to make cittern-like instruments in England to cater for the demand from the developing English Moravian communities".

In an advert published in the Public Advertiser on November 17, 1755 (GDN Z2001070925, BBCN) Mr. Hintz claimed that he was "the Original Maker of that Instrument, call'd The Guittar or Zittern, who has for many Years made and taught that Instrument [...] He teaches common notes in the best and easiest manner". There is good reason to assume that Hintz had in fact "invented" the guittar. By all accounts he was an extremely gifted craftsman. It would have been no problem for him to develop it from the citterns he knew in Germany which often also "had ten wire strings" and "it is possible that he introduced a modified version to Britain". He is also reported to have played that instrument for a dying friend already in 1751 (Holman, p.145-6).

It would be interesting to know if Miss Macklin used one of his instruments or if she knew him personally. He never referred to her in any of his adverts. Nonetheless Mr. Hintz struck gold because Maria Macklin had promoted the guittar most effectively on stage in The Englishman In Paris and The Chances. He became a highly successful businessman. From then on he built guittars and other musical instruments no longer only for his Moravian brethren but for the general market, for the "fashionable beau monde, which placed a premium on novelty" (Holman, p. 162).

Hintz even supplied the Royal Family with guittars and his instruments were also sold outside of London. Neil Stewart opened a music shop in Edinburgh in 1759 and in his first advert he offered "guitars of all sorts, particularly a parcel made by the famous Frederick Hintz, who was the first maker of that instrument in London, and is at present guitar maker for the Royal Family, and most of the nobility in England" (Caledonian Mercury, November 14, 1759, p.3, BNA). Four months later Stewart announced the arrival of another big parcel from London:

"At the sign of the Violin and German flute, in the Exchange, Edinburgh, Has newly arrived from London, A Large Assortment of Guitars, From two guineas and a half to seven guineas. Guitars to play with the Bow. Small Guitars of two sizes; the smallest may be managed by young ladies from seven to ten years old, and the others by ladies from ten and upward. Mandolins and Mandolines, to be played in the same manner with the Guitar, All made by the famous Frederick Hintz" (Caledonian Mercury, March 26,1760, p. 3, BNA).

Hintz himself also placed adverts in regional newspapers:

"Frederick Hintz, Guittar-maker to her Majesty and the Royal Family, proposes to send to any Lady or Gentleman in Scotland or Ireland, that will favour him with their commands, Extraordinary Fine Guittars, both in workmanship and sound. The best sort for five guineas, another sort for four, and another for three guineas, carriage included. As also, the best guittar strings, at a reasonable rate - Please direct at his musical warehouse, the corner of Ryder's Court, Leicester Fields" (Caledonian Mercury, August 16, 23 & 30, 1762).

In Thomas Mortimer's Universal Director (1763, Part II, p. 51) he was also listed as "Guittar-maker to her Majesty and the Royal Family" and his shop must have been a veritable treasure trove of exotic instruments. He sold "Guittars, Mandolins, Viols de l'Amour, Viols de Gamba, Dulcimers, Solitaires, Lutes, Harps, Cymbals, the Trumpet-marine, and the Aeolian Harp" (see also Holman 2010, p. 148).

A letter published in the St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post, October 27, 1763 - October 29, 1763 (GDN Z2001257890, BBCN) gives some more insights into his activities:

"As there has been lately advertised, what is called a new-invented Guitar with eight strings more in the Bass, it is thought necessary to acquaint the Publick, that Mr. Hintz, Guittar Maker to Her Majesty and the Royal Family, invented and made this Kind of Guittars 3 Years ago; but, as he found that the Ladies were not at that time disposed for them, from some Circumstances of Inconvenience which they thought attended the additional Number of Strings, he did not make them publick: But has, nevertheless, found it necessary always to keep by him a certain Quantity ready-made and finished in the best Manner. He as also a Guitar called the Tremulant, a De L'Amour Guittar, with a Lute Stop; a Guittar to be played with a Bow, as well as with the Fingers; All of which were invented by him, and are made and sold at his House [...]".

In the '60s Hintz also compiled two books:

- A Choice Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes set for the Cetra or Guittar, Printed for Robert Bremner, London [ca.1762 or later] (see Copac)

- A Choice Collection of Airs, Minuets, Marches, Songs and Country Dances &c., By several eminent authors, Adapted for the guittar, Printed for the Author, London [ca. 1765] (see Copac )

Both collections must have been quite popular. They were still listed in Bremner's Catalogue of Vocal and Instrumental Music, March 1782 (p. 4) and in Preston & Son's Additional Catalogue of Bremner's stock published in 1790 (p. 10).

Frederick Hintz died in 1772 and his household equipment as well as his stock of instruments were sold in an auction:

"To be sold by Auction, By Mr. Elderton, On the Premises, On Thursday, August 13, and he following day, The Genuine Stock in Trade, Household Furniture, Linen, China, and Pictures of Mr. Hintz, the corner of Riders-court, Newport-street,Musical Instrument-maker, deceased, consisting of Guittars, Lutes, Mandolines, Harps, Harpsichords, Spinnets, Clavichords, Forte Pianos, Eolian Harps, German Harps, Dulcimers, Psalteries, Violins, Tenors, Bass Viols, Viol da Gambals, Trumpet Moriens [sic!], German Flutes, &c.It is allowed that the late Mr. Hintz, was one of the first Guittar-makers in Europe; and that his instruments in general were very excellent [...]" (Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, August 7, 1772, GDN Z2000824622; see also Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, August 11, 1772, GDN Z2000372644, BBCN: "[...] one of he best Guittar-makers in Europe").

There is no convincing evidence that any other instrument maker was building and selling guittars before Hintz started doing so. It seems the earliest extant guittar is one made by J. C. Elschleger, about whom nothing else is known except that his name strongly suggests that also was of German origin. This instrument has been dated as from 1753 (see Holman, p. 146; undated in Tyler 2009, p. 13). But that year Miss Macklin was already playing her "pandola" on stage.

Three guittars made by Remerus Liessem have survived, the earliest apparently from 1756 (see Tyler 2009, p. 14). Judging from his name he could have been either from Germany or from the Low Countries. In 1757 he published Il Passa tempo della Guittara. Twelve Italian Airs for the Voice, accompanied by the Guitar or Harpsichord by Italian music teacher Santo Lapis, one of the earliest books for this instrument. Lapis had recently arrived in London and at that time lived at Liessem’s "Music Shop in Compton-Street, St. Ann's, Soho" (see Public Advertiser, October 6, 1757, GDN Z2001074179, BBCN). His guittars had a good reputation and his "very best ones" were also sold by Neil Stewart in Edinburgh "at five guineas" (Caledonian Mercury, November 14, 1759; see also January 23 & March 26, 1760, BNA). But he died in 1760 and his widow offered a part of his stock for sale:

"Reinerus Leissens [sic!], Musical Instrument Maker, being dead, his widow gives this Notice to the Publick, that she intends reducing his Stock of Instruments that are now finished, by an immediate Hand-Sale of them, consisting of Violins, Tenors, Violoncellos, Violin d'Amour, Guittars, Mandalins, Lutes, Basses, &c. The Tone and Neatness of his Work are too well known to need Recommendation in a Publick Paper [...]" (Daily Advertiser, April 23, 1760; GDN Z2000152047).

In 1757 composer and publisher James Oswald sold in his shop the "best Guittars [...] carefully fitted, by an eminent Master" (see London Chronicle, June 21, 1757-June 23, 1757, GDN Z2001662974, BBCN) but it is not known who had made these instruments. Violin maker Benjamin Banks from Salisbury also built some guittars. In an Illustrated Catalogue of a Music Loan Exhibition in 1904 a "Cittern, English", "probably" made by him, is dated as from 1750 (p.138) but that seems to me highly improbable. In another catalogue of this exhibition it has been left undated (p. 114, No. 1186). Both catalogues list another "Cittern, English. - Made by Benjamin Banks, of Salisbury, in 1757" (p. 113, No. 1181) and this date sounds much more reasonable.

Early in 1758 John Tyther's Cane and Music-Shop in London offered - besides assorted talking parrots and singing birds - "one of the best English-made Guittars to be sold cheap" (Public Advertiser, February 3, 1758, GDN Z2001074736, BBCN). But Mr. Tyther was more of an expert for birds than for guittars and I don't think he had built this instrument himself. In March that year a Mr. Richter, Musical Instrument Maker, in Tower-Street put up for sale "a large number of very fine and good Guittars of new Invention, which keeps extremely well in Tune, and the Strings not liable to crack, very suitable for a Lady to tune herself, cheaper than any in London. At the same Place is Instruction for the above Guittar" (Public Advertiser, March 3, 1758, GDN Z2001074859, BBCN). Nothing else is known about guittar maker but his name suggests that he also was of German origin. The same month organ-maker William Hubert van Kamp jumped on the bandwagon and sold "Guittars after the newest Make and Fashion, and stand the longest in Tune" (Public Advertiser, March 22, 1758, GDN Z2001074943, BBCN).

Another extant guittar by one Mr. Hoffmann has been dated as from 1758. In fact A. C. Hoffmann had a shop in Chandois-Street together with Michael Rauche. But this partnership ended in May 1758:

"A. C. Hoffmann, Maker and Dealer in all Sorts of Musical Instruments, begs leave to inform the Public, that the Partnership between him and Mr. Rauche being disso'ved, he continues to carry on the Business in Chandois-Street, Covent Garden, opposite to Bedfordbury, two Doors from the farmer Shop, and humbly begs the Continuance of the Favour of his Friends and Customers. Gentlemen and ladies may be immediately supplied with Guittars, Lutes, &c. of the best and truest Make" (Public Advertiser, May 30, 1758 , GDN Z2001075261, BBCN).

Both Hoffmann and Rauche surely have built guittars before 1758 but it is not known when they started their business. I found only one more advert by Hoffmann. In the Public Advertiser on December 2, 1758 (GDN Z2001076109, BBCN) he offered "extraordinary good French Horns [...] just imported" but didn't forget to note that he also sold "Guittars, Lutes [...] of the best and truest Make" at his "Music Warehouse". Since then nothing more was heard of him. Perhaps he retired or died shortly afterwards.

It seems that towards the end of the 1750s this instrument was easily available everywhere. Robert Bremner in Edinburgh offered "Guitars from two to six Guineas" on the title page of his book Instructions for the Guitar that was published in November 1758. It is not known when he had started to sell them. At least guittars must have been already available there otherwise it would have made sense to publish a tutor. Also it is not clear if he only sold instruments imported from London or if they were already built in Scotland. His local competitor Neil Stewart - who opened his shop in November 1759 - at first only sold instruments made by Hintz and Liessem (Caledonian Mercury, November 14, 1759, p. 3, BNA). But since March 1760 he also offered "Guitars made at Edinburgh, equal to any made in Scotland, from one guinea and a half to three guineas the best". They were a little bit cheaper than Hintzen's original products that were sold for "five, six, and seven guineas" (Caledonian Mercury, March 26, 1760, p. 3 & January 23, 1760, p. 3 BNA).

In 1761 Stewart also began to sell guittars made by Michael Rauche, the former partner of J. C. Hoffman. In his adverts he claimed that Rauche and Hintz were "reckoned to be the best makers of that instrument in London" (Caledonian Mercury, January 17, 1761, p. 2, also July 29, 1761, p. 3 & April 28, 1762, p. 1, BNA) . In fact his guittars always had an excellent reputation and they were for example recommended by Ann Ford who wrote in the introduction to her Instructions in 1761 that they had the "best tone" (Tyler 2009, p. 16).

Rauche's first advert was published in the Public Ledger or The Daily Register of Commerce and Intelligence on September 5, 1761 (GDN Z2001238006, see also Public Advertiser, October 6, 1761, GDN Z2001082855, BBCN) but for some reason here he preferred to promote a "Most Beautiful and Complete Cabinet of Minerals, consisting of Gold, Silver, Quicksilver, Cobalt, and all other Sorts of Ores, which has been collecting towards Thirty Years [...] from the most distant Parts of the World [...] with many other Curiosities too tedious to Mention". It seems he had other interests, too or at least sometimes a "music warehouse" had to offer more than only musical instruments to attract customers. But in the last line he also noted that he had "Completest Guittars, Mandolins, Lutes, Best Strings of all Sorts, &c.".

In 1763 Rauche started publishing music for the guittar. In two adverts in January that year he offered an impressive range of books, for example works by F. T. Schuman, Rudolf Straube, Charles Clagget and the Portuguese guittar player Roderigo Antonio de Menezes. Some of them were reprints of older publications like Schuman's first set of Lessons but most of them were new. In May he announced some more items: two song collections by Ghillini di Asuni as well new Lessons by Menezes. He also sold Ann Fords Instructions for both the guittar and the musical glasses (Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser, January 6, 1763, GDN Z2000341655; Public Advertiser, January 17, 1763, GDN Z2001088026 & May 6, 1763 GDN Z2001089547, all BBCN).

In spite of this promising start Rauche rarely published during the next two decades. Most notable were two new works by Rudolf Straube, the Mecklenburg Gavotte for the harpsichord and the Three Sonatas for the Guittar, both in 1768 (see BUCEM II, p. 985). His last known advert - in 1774 - was for D. Ritter's Choice Collection of Twelve of the most favourite Songs sung at Vauxhall, adapted for the Guittar (Public Advertiser, February 11, 1774, GDN Z2001147689, BBCN; see also Copac). Interestingly some works by Schuman, Straube, Ghillini and Menezes that had been originally published by Rauche were reprinted in 1776/7 by Mary Welcker (see Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, November 9, 1776, GDN Z2000843506 & February 19, 1777, GDN Z2000844344, BBCN).

It is quite possible that he only sold the rights to these books to Mrs. Welcker because he needed some money. It seems that he had some serious financial problems at that time. Shortly thereafter, in 1778 Mr. Rauche even was "Prisoner in the King's Bench Prison in the County of Surry" and applied for release according to the most recent Act for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors (see for example London Gazette, June 6, 1778 - June 9, 1778, GDA Z2000735857, p. 5, BBCN).

But apparently Rauche survived his stay in the notoriously unhealthy debtors' prison and even got his shop back or at least could set up a new one. He most likely died in 1784. In an advert in the Morning Herald on January 20,1785 (GDN Z2000919031, BBCN) a Mr.Buckinger, also an instrument maker and music seller of German origin, announced that he was "the only successor to the late Mr. Rauche, whose Guittars ever justly bore the preference, he continues to make them of the same pattern, having purchased his stock and utensils [...] N.B. The Guittar taught agreeable to the manner of the late Mr. Rauche". It is obvious that Michael Rauche never became as wealthy as Mr. Hintz but at least it is good to see that his reputation was still high at the time of his death.

It seems that during the '50s very few English instrument makers tried their hands at guittars. We only know of Edward Dickenson (Tyler, p. 12) and of the above-mentioned Benjamin Banks from Salisbury. If they were more their names have been lost. Not at least it is not clear who built the instruments sold for example by Oswald in London and Bremner in Edinburgh. Only since the 1760s native guittar makers played a more significant role. Most important was John Preston who introduced both the so called watch-key tuning in 1766 and the piano forte box in 1786 (see chapter II.1).

Most of the earliest guittar makers were of German or Dutch origin: Hintz, Elschleger, Liessem, Richter, van der Kamp, Hoffmann, Rauche. At that time "Germans were attracted to London as Europe's most vibrant commercial centre, providing opportunities for enterprise and entrepeneurship" (Jefcoate 2001, p. 503). Instrument-makers found there a lively music scene and many potential clients with deep pockets who were happy to shell out some of their money for products of high quality, especially if they had some novelty value. A guittar by Hintz was a luxury item. It cost up to 7 guineas and not everybody could afford it. Rauche, Liessem & co. were surely familiar with German citterns and they were quickly able to satisfy the growing demand for this fashionable toy. And like Hintz they could supply their customers with other exotic and unusual musical instruments.

4. Music for the Guittar 1756 - 1763: An Overview

The first one to publish a book of music for the guittar was Thomas Call who - as already noted - had made himself a name as a teacher for that new instrument. At least it was the first exactly dateable publication. On August 26, 1756 he placed an advert in the Public Advertiser (GDN Z2001072239, BBCN) to announce that he had "composed a Set of Airs for the use of the Guittar only, which will be very helpful for the true Exercise of the Fingers [...] Ladies who chuse to be Subscribers to this Book, are desired to send Word at Mr. Call's Lodging [...]". His "Book of Airs and Songs, principally adapted" for the Guittar was then published in November "and to prevent Imposition by Piracy or false Copies, this Book will be sold only by the Author" (Public Advertiser, November 5, 1756, GDN Z2001072556, BBCN). Sadly there are no extant copies of this work. Interestingly in the second advert also he took a swipe at other teachers:

"[...] Mr. Call cannot help taking Notice, that as Numbers of Ladies have learnt this Instrument, they have had different Masters for their Instructors, one teaching out of one Key, another out of another Key, and Ladies who are not thoroughly acquainted with the Grounds of Music cannot see thro' the Mystery, but taking it for the most perfect Plan that shews the open String in the plainest Manner, without considering the Difficulty that is attended with the higher Parts of the Instrument. My Method of teaching and my Book is all, from the well known Plan of the Harpsichord, taking every Key in its natural Order, without so much additional Trouble of Transposition".

Probably at around the same time another a little booklet called The Ladies' Pocket Guide or The Compleat Tutor for the Guittar was brought out by publisher David Rutherford (Kidson, British Music Publishers, p.113) The exact date of publication is not known so I can't say if it was available before Mr. Call's book. This tutor included some "Easy Rules for Learners" as well as a "choice Collection of the most famous Airs":

"Its author describes a somewhat primitive thumb and forefinger technique, which involves playing the bottom three strings with the thumb and all the notes that lie on the top three strings with the forefinger. As innumerable simple melodies could be played using only the top three strings, this forefinger method would be quite adequate, especially for the novice with little musical or technical ability" (Coggin 1978, p. 210).

In March 1757 a Mr. Meackham, not a music publisher but a a hosier and glover, also announced a book of "Instructions for playing on the Cittern or Guitar" and promised instant success: "a Scale of the Notes, and the Finger Board of the Instrument are prefix'd, whereon the Stops and Frets are so pointed out, that any Person may, without other Assistance, be capable, in a very few Days, to play on this Instrument" (London Evening Post, March 8-10, 1757, GDN Z2000660255, BBCN).

But the great flood of music books for the guittar only started in June 1757 with James Oswald's Eighteen Divertimentis or Duetts, properly adapted for the Guittar, or Mandolin (see McKillop 2001, p. 134). Oswald (1710 - 1769) was the "most prolific and successful composer of 18th-century Scotland" (NG 18, pp. 790-1, see also Kidson, BMP, pp. 84-87 & BDA 11, pp. 122-124 ). At first he worked in Dunfermline and Edinburgh but then moved to London and set up shop there in 1741. He made himself a name as a publisher, music teacher, arranger and cellist. In 1761 he was even appointed chamber composer to King George III.

James Oswald was among the first composers and publishers to recognize the potential of this new market segment created by the guittar and he was at partly responsible for this flood of new music for this instrument. From 1758 to 1760 he brought out a collection of tunes called Forty Airs for two Violins, German Flutes, or Guittars , a booklet of songs by popular singer Catherine Fourmantel ("all transposed for the Guittar") and a set of Twelve Divertimentis, his ""most important contribution to the guittar literature" (McKillop 2001, p. 135; see also RobMcKillop's website for a pdf-copy of the book and recordings of these pieces). Oswald also published Twelve Serenatas, for a Guittar by Antonio Pereya da Costa, most likely a pseudonym for himself (see McKillop 2001, p. 134) as well as the XII Favourite Lessons or Airs for two Guittars by young composer George Rush and he was amongst the music sellers stocking Santo Lapis' Guittar In Fashion.

Not at least he also offered a Compleat Tutor for the Guittar, but that tutor was "not 'compleat' in any way, this publication consists of a single-page explanation of the fingering of the major scale in G and C, and another single page explaining note values and rests" (McKillop 2001, p. 136). The rest of the booklet was made up of popular songs arranged for the guittar. This tutor was the first volume of the so called Pocket Companion for the Guittar of which at least five more parts were published that included many more arrangements that were "accessible to most competent amateurs".

Between June 1757 and December 1763 more than 70 music books for guittar players were published, most of them in London but a small number also in Edinburgh. This was quite a lot if we take into account that not a single publication was available in 1755 and only one or maybe two in 1756. One may assume that at this time, more than four years after Maria Macklin had first used her "pandola" on stage, enough gentlemen and ladies were able to play the guittar. Now the publishers had to satisfy the increased demand for new printed music for this instrument. Nearly all of this publications were aimed at amateur musicians, especially the ladies who played the guittar at home.

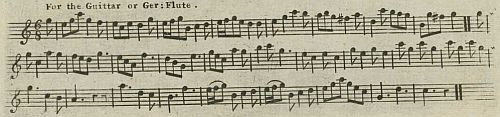

Interestingly a considerable number of these publications were not written specifically for the guittar. It seems that some publishers and composers treated it at first simply as one more melody instrument and placed "for the guittar" on the title pages of their tune collections so they could get a share of this new cake without much effort. For example the Twenty-four Duets for two French Horns, two Guittars, or two German Flutes by French horn player Joseph Real and published by Thompson and Son in October 1757. But this book had been first announced in September - "speedily will be published" - only as duets for "two French Horns or German Flutes" (see Public Advertiser, September 15, 1757, GDN Z2001074085 & October 27, 1757, GDN Z2001074278, BBCN). In the meantime someone must have thought it a good idea to add the "guittar" to the title page.

Most notorious in this respect was music publisher John Walsh. His very first publication aimed at guittar players were the Forty select Duets, Ariettas and Minuets for two Guittars or Mandavines, by the best Masters that came out the same month as Oswald's Eighteen Divertimentis. But Walsh hastened to add on the title-page that these "airs are also proper for two German flutes or French horns" (see the catalogue record of the BL via Copac). Other example can be found in the bibliography.

More useful were some more tutors. The most important were Robert Bremner's Instructions For The Guitar that were published in Edinburgh in November 1758 (a pdf-copy of this book is available on Rob McKillop's website). Bremner was one of the most important British music publishers in the second half of the 18th century and his publications were often of high quality. It is not clear if this booklet was written by Bremner himself or by possibly his son Robert "who had been sent to to London to study the guitar with Geminiani" (David Johnson in NG 4, p. 314). Bremner, jun. was a musician who had his first concert in December 1755 (see Caledonian Mercury, December 11, 1755, p. 2, BNA). It is not known if he was already playing guittar at that time but - as already noted - by 1759 he worked as a teacher for that instrument.

The first half of Bremner’s tutor offered detailed and helpful instructions (quoted by Armstrong, p. 8-14 and on Rob McKillop's website, see also Coggin, pp. 210-12) while the rest of the book was made up of more or less easy arrangements of popular songs that everybody was familiar with, for example "Allen a Roon", "O'er The Hill And Far Away", "Johnnie Faa" and "Birks of Endermay". Bremner tuned the guittar to a C-major chord and all these arrangements were in this key. We should remember that Thomas Call still knew "six different ways of tuning" and if I understand some of the explanations in his adverts correctly he was also able to play the guittar in more than one key (see chapter 1.2). Italian violinist and teacher Giovanni Battista Marella used an A-major tuning and in February 1757 he had published a book of lessons "in every key, both flat and sharp". James Oswald had at first also tried out a "G"-tuning (see McKillop, p. 135-6). It seems at some point the C-major tuning became standard and arrangers and composers preferred to stay in the key of C because, as Rob McKillop (2001, p.136) has noted, "on a wire-strung guittar, the instrument never sounds as well as in the key of the chord of the open strings".

By all accounts Bremner's Instructions became the most popular tutor. A second edition was already published in Edinburgh in 1760 and it was later also reprinted in London where Robert Bremner had opened a shop in 1762. The book remained available at least until the end of the century (see Catalogue Bremner, 1782, p. 4 & Additional Catalogue, Preston And Son, 1790, p. 10).

In November 1760 Bremner also published Francesco Geminiani's Art of Playing the Guittar or Cittra (see Coggin, p. 212-3) . It is not clear why the famous composer and violinist Geminiani (1687 - 1762), author of the influential Art of Playing the Violin (1731), became interested in this instrument. This was a very ambitious work and the guittar-parts were written in tablature that had become uncommon at that time. He claimed that the guittar "is capable of very full and compleat harmony" (quoted from Coggin, p. 213, see also McKillop 2001, p. 143-4) and interestingly most of the pieces could also be played on the violin:

"These compositions are contrived so as to make very proper solos for the violin: and as all the shefts and graces, requisite to play in a good taste, are distinctly marked, it must be of great use to those who aspire to play that instrument" (from Bremner's advert in the Caledonian Mercury, 26.11.1760, p.3, BNA, also quoted by Coggin, p. 213).

Guittar tutors were also available from publishers John Johnson and Thompson & Son. Not at least multi-instrumentalist Ann Ford wrote a book of Lessons and Instructions to "attain Playing in true Taste" (see Holman 2010 and Coggin, pp. 215-6). Besides that everybody interested in learning to play the guittar could choose between a considerable number of books of "lessons", for example by composers Giovanni Battista Marella, Charles Barbandt, George Rush, Frederic Theodor Schuman, Charles Clagget, William Bates or Rudolf Straube. There were also some sonatas, serenatas, "easy minuets", solos and duets. The great Giardini even wrote Six Trios for the Guitar,Violin, and Violoncello.

Additionally music publishers supplied their customers with collections of songs "adapted for the guittar". This usually meant that they were transposed to the key of C. Among the first was Robert Bremner in 1760 with his Twelve Scots Songs, a "veritable 'Greatest Hits' package of the eighteenth century (McKillop 2001, p. 133). The same year London publisher David Rutherford offered Twelve of the most celebrated English Songs which are now in vogue, neatly adapted for the Guittar and Voice. More collections followed, for example a selection of Favourite Italian and English songs from Galluppi, Handel etc taken from the repertoire of popular singer Miss Stevenson or a book called The Lady's Amusement with Favourite French & Italian Songs, Airs, Minuets & Marches, none ever before Publish'd, that were "adapted for the guittar" by Michael Ghillini di Asuni, both published in 1762.

Especially popular were collections of songs from successful shows. For example in 1759 publisher C. Jones put out All the Tunes in the Beggar's Opera, transposed into easy and proper Keys for the Guittar and the following year Robert Bremner offered The Songs in the Gentle Shepherd, Adapted for the Guitar (see McKillop 2001, pp. 130-132). In 1762 both John Johnson and Thorowgood & Horne published the songs of Thomas Arne's Artaxerxes "correctly transposed" not only for the German flute and violin but also for the guittar and in 1763 at least five music publishers - Walsh, Johnson, Thorowgood & Horne, Rutherford and Rauche - threw books with guittar arrangements of songs from Arne's immensely popular comic opera Love In A Village on the market.

But besides all this frivolous music the guittar players were also supplied with more serious songs. The Magdalen Hospital was founded in 1758 and Thomas Call obviously became organist at its chapel. In 1760 he compiled a collection of tunes and hymns sung there, "properly adapted" not only for the organ and harpsichord but also for the guittar. William Yates, organist and teacher for the harpsichord put together A Collection of Moral Songs or Hymns for a Voice, Harpsichord and Guittar in 1762.

The guittar was and remained an instrument used nearly exclusively for domestic music-making. Professional musicians only rarely played it in their concerts. As mentioned above Marella - in Oxford in 1756 - seems to have been the first one but only very few of his colleagues followed his example. German lutenist Rudolf Straube performed "several Lessons upon the Arch-Lute and Guittar in a Singular and Masterly Manner" at a concert in Bath on January 1,1759 (Holman 2010, p. 153). Violinist Thomas Pinto played a "Solo on the Guittar" at a benefit for cellist Emanuel Siprutini in March 1760 (Public Advertiser. March 20, 1760; Issue 7916, GDN Z2001078435). The legendary Ann Ford used the instrument in her concerts in 1760 and 1761. For example in her second show on March 25, 1760 the audience heard a "Concerto on the guittar" and in the third on April 4 "a Lesson and Song accompanied with the Guittar" (see Holman 2004).

German child prodigy Gertrude Schmeling - who later became the famous singer Madame Mara (see BDA 10, pp. 77-87) - was on tour in England since 1759. She sang and played the violin. While laying sick for some weeks in 1760 she also learned to play the guittar:

"Ich bekam indessen den Keuchhusten, und da ich deshalb zu Hause bleiben mußte, so lernte ich die Guitar [...] welche damals das Mode-Instrument war und von allen Damen gespielt wurde. Ein deutscher Instrumentenmacher hatte eben eine mit einem tiefern Boden als gewöhnlich verfertigt, sie mit stärkern Saiten bezogen, wodurch sie einen schönen vollen Ton bekam [...] Da traf sichs, dass ein Porugiese Namens Rodorigo nach London kam, er spielte die spanische Guitar vortrefflich [...] er erbot sich mir Untericht zu geben, ich äußerte einige Zweiffel, weil mein Instrument nicht von der Art wäre als das seine, er erwiederte, man könnte auch aus dem meinigen Vortheile ziehen, wenn man sich nur zu benehmen wüßte. Darauf spielte er mir etwas auf meiner Guitare vor, und ich was außer mir für Freuden. Er gab mir einige Musikalien, und lehrte mich einige Arien nach seiner Art zu accompagnieren" (Selbstbiographie Mara, 1875, p. 514).

"Rodorigo" most likely was the Roderigo Antonio de Menezes whose Divertimenti and Lessons were published by Rauche in 1763. Gertrude then used this instrument in her concerts, much to the pleasure of her audience:

"Miss Schmeling, a native of Hesse-Cassel, in Germany [...] though but ten years old, not only readily speaks several languages [...] and sings charmingly in concert, &c. but also plays surprisingly well on the violin and guittar" (London Magazine, Vol. 29, p. 489, about a show in Exeter).

In an advert for a concert in Oxford in March 1761 it was announced she would perform - besides "a Concerto on the Violin and also several Songs both English and Italian" - a "Variety of Lessons on the Guittar" (Oxford Journal, March 28, 1761, p. 2, BNA ). In Dublin the 50 year old wife of a Colonel "fell in love" with her guittar-playing and asked the girl to give her some lessons (Selbstbiographie Mara, 1875, p. 516).

French violin player Etienne Piffet came to London in March 1762. At his first concert there on March 16, a benefit for the famous singer Tenducci, he played the "First Violin with a Concerto and a Solo. But in an advert for his own benefit in May that year it was announced that he also "will sing several Songs accompanied with a Guittar". So it seems that quickly learned to play that instrument, perhaps as a favour to his English audience (see Public Advertiser March 13, 1762; GDN Z2001084161; May 26, 1762, GDN Z2001085001; see also May 17, 1763, GDN Z2001089733, BBCN, the advert for another benefit).

I only found these few examples. Perhaps there were some more, but it can not have been that much. One may assume that most professionals were skeptical about the guittar and saw it more as a toy for the amateurs than as an instrument for the serious music-making. Nonetheless a considerable number of musicians had to make themselves familiar with this "toy" because it was so popular among their clientele. At least for some of them it surely proved to be a profitable sideline.

Interestingly many of those who wrote music for the guittar, taught that instrument or played it on stage were Italians. But that should come as no surprise. At that time Italian music was highly popular and musicians from Italy were busy all over Europe (see for example the articles in Strohm 2001). London was an an especially attractive destination: "Italy had the reputation for producing the best singers and composers, while England had the reputation for paying them" (Berry 2011, p. 41). Italian Instrumentalists of all kinds also flocked to London (see f. ex. McVeigh, 1983, 1989, 2001; Sadie 1993; Lindgren 2000) and Italians were "most sought after" as music teachers (Leppert 1988, p. 56).

Therefore we find an interesting cross-section of Italian musical immigrants and visitors among those who took up the guittar and tried to get a share of that new cake: Santo Lapis, a wandering music teacher who also had worked for some time as an opera impresario; Felice Giardini, a famous violin virtuoso and prolific composer; cellist Pasqualino di Marzi, a hardworking orchestra musician; conductor and violinist Giovanni Battista Marella; legendary composer Francesco Gemiani; a complete unknown like one Luigi Senzanome who obviously worked outside of London and is only known from a single publication; a gentleman musician like Michael Ghillini di Asuni, who over the course of more than twenty years regularly published guittar books until he was appointed consul of Cagliari. But of course not everybody was as successful as he would have wished. For example Lapis - after some years in London - moved to Bath, then settled for some time in Edinburgh and later possibly went to Ireland. We don't even know where he died.

Of course also native teachers and composers were busy in this field, but at least some of them also showed Italian colours. Thomas Call offered to teach the instrument "in Italian, Spanish, or German Manner" - obviously there was no English "manner" -, George Rush wrote his XII Lessons after his return from Italy and Robert Bremner, jun. had studied with Geminiani. The guittar had been invented and introduced by a German instrument maker and was at first mostly built and sold by Germans. But one should remember that Miss Macklin played the "pandola" to an Italian song in The Englishman in Paris and in The Chances she was "Dress'd after the Old Italian and Spanish Manner". For the English audiences this instrument was not so much connected to German culture instead it clearly had an exotic Italian touch. This may have been another reason for the guittar's great popularity.

II. The Next Fifty Years

1. Music For The Guittar Until 1800: An Overview

In the early 1760s the guittar was one of the most popular instruments for domestic music-making. Young Gertrude Schmeling from Germany noted at that time that it was played by "all the Ladies" (Selbstbiographie Mara, 1875, p. 516). But this fashionable instrument had several shortcomings and from the start there were attempts to "improve" it and expand its possibilities. Already in 1757 Liessem had built a guittar with additional bass strings (see Galpin, plate 8, Nr. 2). Later Rauche constructed a "Lyre [...] an Instrument that imitates the Harp as well as the Guittar" (Public Advertiser, January 13, 1766, GDN Z2001108850, BBCN). Frederick Hintz tried his hand at a guittar "with eight strings more in the Bass", one "called the Tremulant, a De L'Amour Guittar, with a Lute Stop; a Guittar to be played with a Bow, as well as with the Fingers" (see St. James's Chronicle or the British Evening Post, October 27-29, 1763, GDN Z2001257890, BBCN). But none of this experiments were successful.

More serious was another problem of the early models: it didn't keep in tune for long. Hintz himself admitted later that this was "a principal Defect, as well as inconvenient" (Public Advertiser, March 17, 1766, GDN Z2001109879, BBCN, also quoted by Holman 2010, p. 139). In 1758 instrument makers Richter and van Kamp both offered guittars that they claimed stayed much longer in tune (see chapter I.4). None of their instruments have survived until today so we don't know how what exactly they did to achieve this purpose. But early in 1766 English guittar maker John Preston introduced the so-called watch-key mechanism "where the strings are attached to metal levers adjustable with a little key similar to that used to wind up a pocket watch" (Holman 2010, p. 148-9, see Andreas Michel, English Guitar, Studia Instrumentorum Musicae). This technique worked much better than the wooden pegs used for the early models:

"John Preston, Of Banbury Court, Long Acre, London, Guittar And Violin-Maker, Begs Leave to acquaint the Nobility, Gentry, and others, that he has lately found out and invented a new Inprovement, or Instrument, for Tuning of Guittars; and which is greatly approved of by all Masters and Dealers in that Branch of Business, in England, Scotland, and Ireland, by many Years Practice and Industry, which never could as yet be found out, though various Attempts has been made for that Purpose,but to no Effect. The Manner of the Tuning the above Guittars is by a small Watch Key, which is done instantly, and will keep the same in that Order for a month together, unless altered.

Whereas others will not keep in Tune for five Minutes, the Peg belonging thereunto are so bad a Nature, that the Nobility, Gentlemen, and Ladies, do not chuse so much with the above Guittars, being so troublesome to tune. The Proprietor of the above Guittars begs leave to say, that, upon producing the same, that all those who are pleased to favour him with their Commands, will be fully satisfied of the above, and shall be waited on immediately. N. B. Please to beware of Counterfeits, as the Proprietor signs his Name on the Belly of the above Guittars; [...]" (London Evening Post, January 7, 1766 - January 9, 1766, GDN Z2000674154, BBCN).

Only two months later Frederick Hintz also announced that he "has now found out, on a Principal entirely new, several Methods, whereby it is much easier and exacter tuned, and also remains much longer in Tune than by any Method hitherto known; which compleat Improvement has met with universal Esteem and Approbation. He has now by him a great Variety finished, in the neatest Taste; where those Ladies who chuse to change their's, or have them altered to this new Improvement, may depend on having them done to the greatest Perfection" (Public Advertiser, March 17,1766, Z2001109879, BBCN; also quoted by Holman 2010, p. 139-9). It is not clear if he was also referring here to this watch-key mechanism or what other "Methods" he had found out. But Preston's invention prevailed and was adopted by all other guittar-makers. Even older instruments were upgraded with this new mechanism as was the case for example with the guittar built by Liessem that can be seen in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (see the images on their website for Museum Number 230-1882).

The guittar remained immensely popular for the next several decades. Therefore this instruments were for example regularly sold at auctions of household equipment. Here I will only quote from one of the many relevant adverts I have found:

"To be Sold by Auction [...] The Genuine and elegant household furniture, pictures, china, some wines, fire-arms, and other curious effects of a Gentleman going abroad [...] consisting of cotton and other beds, feather-beds, &c., a curious counterpane, morine window-curtains, Turkey, and other carpets, mahagony tables, chairs, sophas, desks, and bookcases, cloath-presses, chests of drawers, &c. pier and chimney glasses, in carved, gilt, and painted frames, a small spinnet, an organ, a guittar, a curious air-gun, and other fire-arms [...]" (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, June 2, 1767, GDN Z2000358228, BBCN).

Even those looking for work as a domestic servants sometimes considered it advantageous to point out that they could play and teach the guittar. For example the "young person" applying for a job as a lady's maid in 1775 did not only know about "Millinery, Hair-dressing in the present taste". She also had a "knowledge of music" and was a "compleat Mistress of the Guittar" (Public Advertiser, June 17, 1775, GDN Z2001154725, BBCN). Two years later a "middle-aged man" who "wants a Place, in and out of livery" announced that he also was "very capable of teaching the violin and guittar" (Morning Post and Daily Advertiser, March 26, 1777, GDN Z2000932717, BBCN).

It seems there was also an overabundance of professional teachers. The competition was so great that one music shop even offered lessons for free:

"Music taught Gratis on the Violin, German Flute, or Guittar, by A.B. and C. D. [...] Ladies and Gentlemen are only requested to buy their Instruments, &c. of them, who being the Makers, are determined to sell as cheap as any where in London. They not only teach for a Month as reported by their enemies, bur Persons are attended till they are able to play any common Tune at Sight, on their respective Instruments, the Truth of which will be testified by any Pupil now under their tuition" (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, October 13, 1764, GDN Z2000345853, BBCN).

Nonetheless new teachers appeared and offered their services. For example in 1765 a Mr. Ritter came from Germany and introduced himself to his prospective customers with a somewhat bombastic advert:

"Mr. Ritter, lately arrived from Berlin, who has been musician to a certain great Prince in Germany, well known for his particular attachment to music, takes this method of making his addresses to the nobility and gentry in offering his services. As the German flute and the guittar are his principal instruments, he without vanity, has confidence enough to dare say, that he excells in playing on the said two instruments; and his method to play the guittar is entirely new, on gutstrings, like a lute. Those ladies and gentlemen who will do him the honour to take lessons of him, may depend upon his utmost application to fulfill his engagements in the easiest and most profitable manner to themselves; he engaging himself to bring these who have yet no notion of music, in a short time to perfection [...]" (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, May 10, 1765, GDN Z2000349281, BBCN).

Ritter later published two books: in 1770 Lessons for the Guittar ... Consisting of rondeaus, allemands, minuettes and variations, likewise English & French songs with accompanyments and in 1774 A Choice Collection of xii of the most favorite Songs for the Guittar sung at Vaux Hall and in the Deserter (see Copac). I couldn't find any more information about him but he must have been quite popular. In 1796 a Mr.Stevenson, "Professor of the French and English Guittar", claimed that he had been "a pupil of the celebrated Ritter" (Oracle and Public Advertiser, Thursday, January 28, 1796, GDN Z2001028361, BBCN).

These teachers always promised a lot and I really wonder if they always could keep their promises. A typical example was this anonymous expert:

"Ladies taught the Guittar in a new and easy manner, so that any person, unacquainted with music, may be able to play any common tune in the first month, and to accompany it with the voice [...] it is in this method played in all the keys, sharps, and flats, as well as the naturals which has hitherto been thought a great difficulty" (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, February 27, 1772, GDN Z2000370960, BBCN).

Of course the publishers and composers kept on supplying their customers with new music for the guittar. As far as I can see most of what was thrown on the market was clearly aimed at the amateurs and "dilettanti" and there were only very few more ambitious works. Armstrong (p. 17) even claims that there were "no really fine advanced pieces". But at least it should be noted that German lutenist Rudolf Straube wrote some sonatas for the guittar that were published by Rauche in 1768:

- Three Sonatas for the Guittar, with Accompanyments for the Harpsichord or Violoncello, With an Addition of two Sonatas for the Guittar, accompanyd with the Violin. Likewise a choice Collection of the most Favourite English, Scotch and Italian Songs for one, and two Guittars, of different Authors. Also Thirty two Solo Lessons by several Masters, Printed for M. Rauche, London 1768 (see Public Advertiser, March 29, 1768, GDN Z2001123227, BBCN; BUCEM II, p. 985 and Copac).

According to Coggin (p. 217) this compositions were a "notable exception to the predominantly violinistic style of writing [...] Straube's pieces contain some of the most idiomatic guittar textures in the whole repertory". In 1775 another set of Six Trios for the Guittar, Violin, and Piano Forte, or Harp, Violin and Violincello by Felice Giardini was issued by William Napier (see Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, May 8, 1775, GDN Z2000836937, BBCN; McVeigh 1989, p. 315) and at around the same time Longman, Lukey & Co. published a Sonata for the Guitar with an Accompaniment for a Violin by the great John Christian Bach (see Copac): "With Bach, the overriding sensation is that of a musical genius, toying with the instrument" (Rob McKillop 2001, p. 134).

Otherwise composers preferred to produce lessons and other more easy pieces for the guittar-playing ladies. But the greatest part of the repertoire were songs of all kinds and song collections. Music publishers were anxious to include guittar arrangements on single sheets of popular songs, "scarcely a song or ballad was printed without its being transposed or set for the instrument" (Armstrong, p. 5). A good example is Thomas Arne's "The Cuckow". He had written this song in the '40s for a revival of Shakespeare's As You Like It and it remained popular for the next decades. Some time in the late '70s a version as "sung by Mrs. Baddely" - who performed the song in 1775 (Public Advertiser, May 11, 1775, GDN Z2001154196, BBCN) - was published. Here the publisher included an arrangement for the guittar, but in fact this only meant that the tune was transposed to the key of C (available at IMSLP).

|

Another easily available example (see IMSLP) is Lady Jane Gray's Lamentation to Lord Guilford Dudley, a favourite Scotch song as sung at Vauxhall by Tommaso Giordani, published by Longman & Broderip circa 1785. Only occasionally other keys were used. The guittar arrangement for John Christian Bach's Blest with Thee, My Soul's Dear Treasure (Longman & Broderip, ca. 1780, available at IMSLP) is in the key of F.

Besides that there were numerous songbooks, for example the Collection of the most celebrated Songs set to Music by Several Eminent Authors, adapted for the Guittar published by John Rutherford circa 1774 (available at the Internet Archive):

This is a small booklet with eight popular oldies, all of course in the key of C. Most of them were written by Thomas Arne, for example "Attic Fire" from his Eliza (1754), "Noontide Air" from Comus (1738) or "A Dawn Of Hope" (1745). Joseph Baildon's "If Love's A sweet Passion" was first published in 1750 in The Laurel. A New Collection of English Songs.

In 1775 Longman, Lukey & Broderip brought out A Pocket Book For The Guittar, with Directions Whereby every Lady & Gentleman may become their own Tuner. To which is Added suitable to the refined Taste of the present Age an Entertaining Collection of Songs, Duets, Airs, Minuets, Marches, &c., another typical example of this genre (Lloyd's Evening Post, July 7-10, 1775, GDN Z2000523157, BBCN; available at IMSLP). This was no tutor, there were only two pages about how to tune the instrument while the remaining 100 pages contain an interesting collection of music that everybody knew: instrumentals of all kinds from from "Martini's favorite Minuet" to the "Peasant's Dance in Queen Mabb", from the "Bedfordshire March" to "Mulloney's Jigg" and songs mostly taken from the repertoire of popular performers like Mr. Vernon, Miss Catley, Miss Jameson or Mrs. Weichsell. This book was clearly directed at the amateurs, and it seems that many of them still had serious problems tuning their instrument:

"These directions will I hope be sufficient for ev'ry Lady and Gentleman to tune their own Guitar. It will be more satisfaction to themselves and save a great deal of carriage and expence, to and from the Music Shops; and often when it has been tuned at them, the Strings will probably get out of tune before the proprietor can have he instrument in possession. When ev'ry one of our Obliging Customers can tune their own Guitar, it certainly will be greater satisfaction than the profits arising to the Editors" (p. 5).

This book must have been quite successful. A second edition "with some additions" was published the following year (see Lloyd's Evening Post, February 5-7, 1776, GDN Z2000524311, BBCN). It is listed in a catalogue of Longman & Broderip from circa 1780.

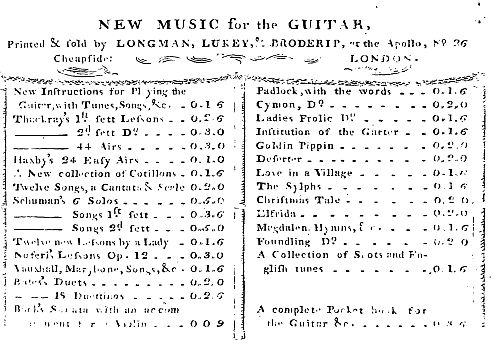

Instrument maker and publisher James Longman (c. 1745-1803) was amongst the music sellers who took particular interest in the guittar. He had arrived in London in 1760, learned the trade as an apprentice at Johnson's music shop and then set up his own business in 1768. Charles Lukey was his partner from 1769 until his early death in 1776 while Francis Broderip joined him in 1777. Longman & Broderip became of the biggest and most important music sellers in London but went bankrupt in 1795 and was divided into two firms, Broderip & Wilkinson and Longman, Clementi & Co., in 1798. James Longman himself died in debtors' prison in 1803 (see Nex 2011).

One of the earliest publications of Longman & Co. was a book called Twelve new Songs and a Cantata, with a compleat Scale for the Guittar (Public Advertiser, September 15, 1768, GDN Z2001126212, BBCN) and it was soon followed by Twenty-four Familiar Airs for the Guittar by one R. Haxby (Public Advertiser, November 24, 1768, GDN Z2001127435). A couple of years later he was able to offer an interesting range of guittar books as can be seen from a catalogue from circa 1780 and the list included in the Pocket Book (p. 2-3).

|

More than a half of his publications for guittar players were songbooks, especially from popular shows like The Christmas Tale, The Padlock, The Golden Pippin or Love In A Village. Besides that there were also a couple of thematic collections like Vauxhall and Marylebone Songs, the Magdalen Hymns or a New Collection of Cotillions as well as two compiled by Frederic Theodore Schuman. The rest of the program was made up of mostly easy pieces for amateurs with Bach's Sonata the only exception. There are some familiar names like Schuman with a set of Solos, Bates with Duets and Duettinos as well as Noferi with some Lessons.

But of course some new names can also be found there. I don't know who this Mr. Haxby was, no other works by him are known. Equally obscure is Mr. Citracini whose Six Divertimentos for two Guitars ,or a Guitar and Violin were first published in 1772 (Public Ledger, June 20, 1772, GDN Z2001230968, BBCN). Another mysterious Italian was Giovanni Battista Canaletti . He is not listed in the catalog but his self-published VI Trii Per Violini due é Cetra. Dedicati all’ Thomas Mayer Esq (ca. 1775, available at IMSLP) were also sold by Longman, Lukey and Co.

The most interesting name here is that of Thomas Thackray who is represented in the catalog with four works: two sets of Lessons, a book of airs and a collection of Divertimenti that were published between 1765 and 1772. Thackray (1740-1793) was from York (see NG 25, p. 326-7, BDA 14, p. 404). He played the violin and violoncello and possibly he also had a music shop there for some time (see Leeds Intelligencer, March 7, 1769, p. 1, BNA).

The first set of Lessons was published in York in 1765 (see NG 25, p. 326, see also Copac with a wrong date). The Six Lessons for the Guittar. Opera Secunda were first announced in the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser on February 4, 1769 (GDN Z2000363223, BBCN). In London John Preston took subscriptions. It seems that this book was a great success. According to Robert Spencer in the New Grove (25, p. 326) there were more than 600 subscribers. His next work, the Twelve Divertimentis for two Guittars, or a Guittar and Violin, Opera 3d was offered in London not only by Preston but also by Longman, Lukey & Co. and John Johnston (Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser , May 1, 1772, GDN Z2000371900, BBNC, see also Copac) and at around the same time Johnston also published Thackray's Collection of Forty-four Airs, properly adapted for one or two Guittars (Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, May 8, 1772, GDN Z2000823950, BBCN). These were his only works for the guittar, later he only wrote a piece for the piano forte called Miss Sophia Wentworth's Minuet (see Copac).

It seems that Mr. Thackray always lived in York and never moved to London permanently. He only played there occasionally, for example in 1776 at Marylebone Gardens (NG 25, p. 326). On April 14, 1778 he was appointed "one of the Musicians to his Majesty" by Lord Chamberlain, the Earl of Hertford (Newcastle Courant, April 18, 1778, p. 4, BNA). This brought him some nice additional income but I have no idea how often he played for the King. At least he remained member of the royal "Band of Music" until his death in 1793 as he was still listed in that capacity in the Royal Calendar from that year (p. 90).