|

Some Notes On The History Of

"The Parting Glass"

(revised 30.3.2012)

I.

"The Parting Glass" is a very popular Irish song with an interesting history. Today many recordings are available and for me the best is still the one by the Clancy Brothers with Tommy Makem from 1959 (on Come Fill Your Glass With Us, Tradition TLP 1032). A live version was included on In Person At Carnegie Hall (Columbia CL 1950, 1963).

Here are the melody and lyrics for this song:

Of all the money that e'er I spent

I've spent it in good company

And all the harm that ever I did

Alas it was to none but me

And all I've done for want of wit

To memory now I can't recall

So fill to me the parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all If I had money enough to spend

And leisure to sit awhile

There is a fair maid in the town

That sorely has my heart beguiled

Her rosy cheeks and ruby lips

I own she has my heart enthralled

So fill to me the parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all Oh, all the comrades that e'er I had

They're sorry for my going away

And all the sweethearts that e'er I had

They'd wish me one more day to stay

But since it falls unto my lot

That I should rise and you should not

I'll gently rise and softly call

Good night and joy be with you all

II.

"The Parting Glass" belongs to a family of songs that can be traced back to the 17th century. The very first evidence for a song with the title "Good Night And God Be With You" is a tune - it's different from the one used for "The Parting Glass" - in the so-called Skene Manuscripts (see Dauney 1838, p. 222), an important collection of music compiled in the 1620s or 1630s. The exact date is not known:

A variant of this tune was then printed for the first time in 1700 in Henry Playford's Collection of Original Scotch Tunes (1700, p. 4). Here the melodic phrase used in the first 1½ bars is already somehow similar to the one later used for "The Parting Glass".

This version of the melody was later included in other popular song collections published during the 18th century (see Bruce Olson, Incomplete Index), for example in:

- Charles Mitchell's ballad opera The Highland Fair; or, Union Of The Clans. An Opera. As it is perform'd at the Theatre-Royal, in Drury-Lane (London, 1731, p. 78; ESTC T002704, available at ECCO; see abcnotation.com). The "musick" of this opera consisted wholly "of select Scots tunes";

- James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion (Vol. 4, 1751, p. 32);

- William McGibbon's Collection of Scots Tunes (1755, Book 4, p. 120):

- James Aird’s A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish And Foreign Airs (Vol. 2, 1782, No. 200, see also abcnotation com);

- Niel Gow’s Part Second of the Complete Repository, of Original Scots Tunes [...], 1802, p. 38; see also The Fiddler’s Companion):

This tune was very popular for a long time. According to William Stenhouse (1839, note in Scotish Musical Museum, Vol. 6, ed. from 1839, p. 510) it "has, time out of mind, been played at the breaking up of convivial parties in Scotland" and William Christie wrote in 1876 (p. 299) that it was "still the last played at balls".

III.

The first known text was published in 1654 or - according to another dating - circa 1670 (see Copac) on a broadside called "Neighbours farewel to his friends" (Wing N414B, ESTC R43475 available at EEBO):

Now come is my departing time,

And here I may no longer stay,

There is no kind comrade of mine

But will desire I were away.

But if that time will me permit,

Which from your Company doth call,

And me inforceth for to flit,

Good Night, and GOD be with you all.

For here I grant some time I spent

In loving kind good Company;

For all offences I repent,

And wisheth now forgiven to be;

What I have done, for want of wit,

To Memory I'll not recall:

I hope you are my Friends as yet

Good Night, and GOD be with you all.

Complementing I never lov'd,

Nor talkative much for to be,

And of speeches a multitude

Becomes no man of quality;

From Faith, Love, Peace and Unity,

I wish none of us ever fall;

God grant us all prosperity:

Good Night, and GOD be with you all.

I wish that I might longer stay,

To enjoy your Society;

The Lord to bless you night and day,

And still be in your Company.

To vice, nor to iniquity,

God grant none of you ever fall,

God's blessing keep you both and me!

Good Night, and GOD be with you all.

The Friends Reply.

Most loving friend, God be thy guide,

And never leave thy Company,

And all things needful thee provide,

And give thee all prosperity;

We rather had thy Company,

It thou woulds't have stayed us among;

We wish you much felicity:

Good grant that nothing doe thee wrong.

This text doesn't have much in common with the modern song except of course the last line of every verse. But a variant of lines 3 and 4 of the first verse would later appear as the the opening couplet of the last verse in "The Parting Glass" ("Oh, all the comrades that e'er I had/They're sorry for my going away"). Interestingly one couplet - lines 5 and 6 of the second verse - has even survived until today:

[...]

And all I've done for want of wit

To memory now I can't recall

[...]

This text was reprinted ca. 1700 as the second song on the broadside "Love is the cause of my mourning. Or, the despairing lover. Sung with its own proper tune" (Roxburghe 3.672, available at the English Broadside Ballads Archive). That song had also been published earlier (ca. 1670, see Copac; available at EEBO) and I presume the idea was to combine two popular oldies on one sheet.

Another early text sung to this tune was published - to my knowledge - for the first time in 1764 in William Hunter’s The Black Bird: A Choice Collection of The Most Celebrated Songs and later reprinted in other song collections like The Goldfinch: Or New Modern Songster (Glasgow, ca. 1785, p. 130, at the Internet Archive), The Musical Miscellany (Perth, 1786, p. 346, with music) and even in the USA in the American Songster (1788, p. 204, available at ECCO). But as far as I know it was not printed anymore after 1800:

How happy's he, whoe'er he be

That in his life meets one true friend,

Who cordially does symphatise

In words, in action, hearts and mind.

My kind repects do not neglect

Altho' my wealth or state shall be small

With a melting heart and a mournful eye

I beg the Lord be with you all.

My loving friends, I kiss your hands,

For time invites me for to move;

On yout poor servant lay commands,

Who is ambitious of your love.

He - whose pow'r and might, both day and night,

Governs the depths, makes rain to fall,

To sun and moon gives course of light,

Direct, protect, defend you all.

I do protest, within my breast,

Your memory I'll not neglect;

On that record I'll lay arest,

Hell's fury shall not alter it.

All I desire of earthly bliss,

Is to be free from guilt or thrall;

I hope my God will grant me this:

Good Night, and joy be with you all.

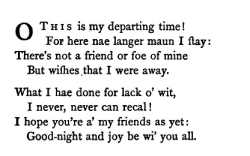

In 1776 David Herd published the second edition of his Ancient And Modern Scottish Songs, Vol. 2. The  chapter "Fragments of Comic and Humorous Songs" included two verses without a title that are clearly recognizable as a relic of the text printed on the old broadside (Vol. 2, 1776, p. 225). Herd was an anthologist, a collector of "old songs" whose work had a great influence on later popular songwriters like Robert Burns. chapter "Fragments of Comic and Humorous Songs" included two verses without a title that are clearly recognizable as a relic of the text printed on the old broadside (Vol. 2, 1776, p. 225). Herd was an anthologist, a collector of "old songs" whose work had a great influence on later popular songwriters like Robert Burns.

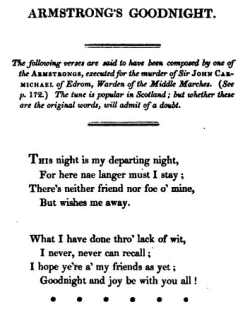

Sir Walter Scott used a slightly different variant of this fragment in the first volume of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (here 5th ed. 1821, p. 287). He called it "Armstrong's Goodnight" and reported that these "verses are said to have been composed by one of the Armstrongs, executed for the mu rder of Sir John Carmichael of Edrom [...] but whether these are the original words, will admit of doubt". Carmichael was killed in a border raid in June 1600 and in November 1601 Thomas Armstrong and Adam Scott were tried and executed in Edinburgh. rder of Sir John Carmichael of Edrom [...] but whether these are the original words, will admit of doubt". Carmichael was killed in a border raid in June 1600 and in November 1601 Thomas Armstrong and Adam Scott were tried and executed in Edinburgh.

As far as I know Scott was the first one to come up with this apocryphal story that has been parroted and embellished endlessly since then. But T. F. Henderson (1902, p. 156) in his comments correctly complains that Sir Walter "neglects to give his authority for this information". There is simply no other reliable evidence that this fragment is in any way related to this incident and that is was ever known as "Armstrong's Goodnight".

In 1757 Oliver Goldsmith wrote in a letter : "If I go for the opera where Signora Columba [Mattei] pours out all mazes of melody, I sit and sigh for [...] Johnny Armstrong's Last Good Night from Peggy Golden". In 1759 he remarked in his essay Happiness in a Great Measure Dependent on Constitution that the "music of Mattei is dissonance to what I felt when our old dairy-maid sung me into tears with 'Johnny Armstrong's Last Good Night,' or the 'Cruelty of Barbara Allen.'" (in The Miscellaneous Works, p. 33/34 and note by the editor p. 34). This is often taken as a kind of corroboration of Scott's story but I presume Goldsmith here refers to the long ballad "John Armstrong's Last Good-Night" (Pepys 2.133 and Roxburghe Ballads 3.513, at EBBA) and not to the fragment.

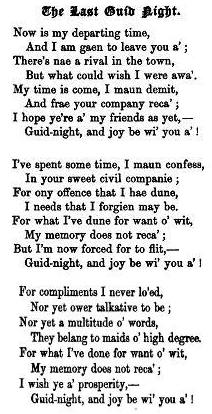

Peter Buchan later claimed that Scott's "eight lines [...] have long been current, and the air to which they are sung popular in Scotland", added two more verses and called it "The Last Guid Night" (1828, p. 121/22, p. 308). But there is no mention of the Armstrongs and I think he simply had found another mutilated relic of the old broadside song. Peter Buchan later claimed that Scott's "eight lines [...] have long been current, and the air to which they are sung popular in Scotland", added two more verses and called it "The Last Guid Night" (1828, p. 121/22, p. 308). But there is no mention of the Armstrongs and I think he simply had found another mutilated relic of the old broadside song.

In 1881 William Christie published a tune for "Gude Nicht, An' Joy Be Wi' Ye A'" in the second volume of his Traditional Ballad Airs (1881, p. 182, with a text by the Baroness Nairne) and noted that this "ancient air [...] was sung to 'The Last Guid Nicht', in Aberdeenshire and also in Morayshire" (p. 299). But this melody is very different from the one we know from the Skene Manuscript.

I think the first one to note the fragment's relationship to the broadside was Henderson in his comments to Scott's Minstrelsy but he also mentioned that there was a broadside from the 17th century called "The Banishment of Poverty by His Royal Highness, J. D. A." that used a tune called "The Last Good-Night" (p. 156/7; see a reprint from 1703 at Word on the Street, NLS). But it is not clear if this was only a different name for "Good Night And Joy Be With You All" or the one of "John Armstrong's Last Good-Night" - also known as "Armstrong's Farewell" - or maybe even another one like the tune of "A lamentable new ballad vpon the Earle of Essex death To the tune of the Kings last good-night " (ca. 1620, see Copac).

In fact Scott - who had serious doubts about that story himself - made it all much more complicated and the Armstrongs are haunting this song since then. But now it's better to leave this behind and turn the attention to Robert Burns who was definitely familiar both with the popular old tune and with the fragment.

IV.

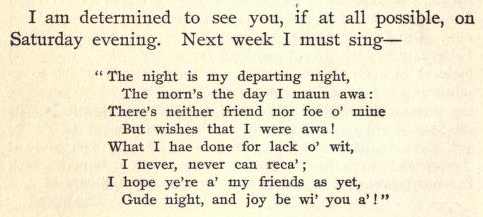

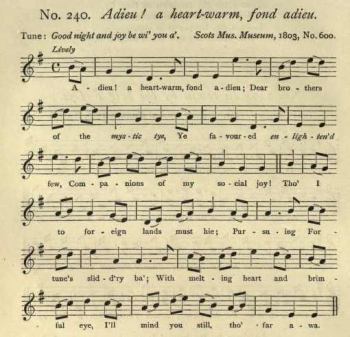

Burns quoted the text in one of  Sylvander’s letters to Clarinda in January 1788 (in: Complete Works of Robert Burns, Vol. 5, 1909, p. 54 ) and also "had a high appreciation of the melody" (Dick, p. 443). He had already used this tune for one of his own songs. It was a time when he had serious problems and thought about emigrating. "The Farewell, To the brethren of St. James Lodge, Tarbolton" was published in 1787 in Poems Chiefly In The Scottish Dialect (here on p. 245 in Poems, Mostly Scottish, undated, ca. 1800; see Dick, p. 214, p. 442/3): Sylvander’s letters to Clarinda in January 1788 (in: Complete Works of Robert Burns, Vol. 5, 1909, p. 54 ) and also "had a high appreciation of the melody" (Dick, p. 443). He had already used this tune for one of his own songs. It was a time when he had serious problems and thought about emigrating. "The Farewell, To the brethren of St. James Lodge, Tarbolton" was published in 1787 in Poems Chiefly In The Scottish Dialect (here on p. 245 in Poems, Mostly Scottish, undated, ca. 1800; see Dick, p. 214, p. 442/3):

Adieu! a heart-warm fond adieu;

Dear brothers of the mystic tie!

Ye favoured, enlighten'd few,

Companions of my social joy;

Tho' I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursuing Fortune's slidd'ry ba';

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I'll mind you still, tho' far awa. Oft have I met your social band,

And spent the cheerful, festive night;

Oft, honour'd with supreme command,

Presided o'er the sons of light:

And by that hieroglyphic bright,

Which none but Craftsmen ever saw

Strong Mem'ry on my heart shall write

Those happy scenes, when far awa. May Freedom, Harmony, and Love,

Unite you in the grand Design,

Beneath th' Omniscient Eye above,

The glorious Architect Divine,

That you may keep th' unerring line,

Still rising by the plummet's law,

Till Order bright completely shine,

Shall be my pray'r when far awa.

And you, farewell! whose merits claim

Justly that highest badge to wear:

Heav'n bless your honour'd noble name,

To Masonry and Scotia dear!

A last request permit me here,—

When yearly ye assemble a',

One round, I ask it with a tear,

To him, the Bard that's far awa.

Burns' version was also published as sheet music:

- Good night and joy be we' you a', a very old Scots song, with a new set of words / written by Robert Burns, Edinburgh 1790? (see Copac)

In 1803 James Johnson used it as the last song in Volume 6 of his Scots Musical Museum (No. 600, p. 620; see also abcnotation.com) . Burns had asked Johnson to also include the "old" text: "Let this be your last song of all in the collection and set it to the old words; and after them insert my Gude night and joy be wi' you a'" (quoted by Dick, p. 443). . Burns had asked Johnson to also include the "old" text: "Let this be your last song of all in the collection and set it to the old words; and after them insert my Gude night and joy be wi' you a'" (quoted by Dick, p. 443).

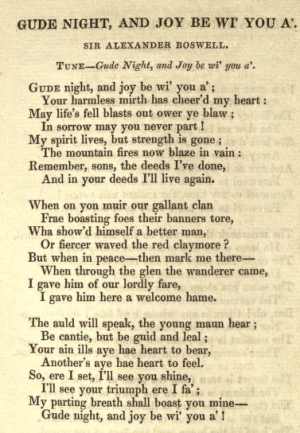

Sir Alexander Boswell, son of James Boswell and a great admirer of Robert Burns also wrote new words for this old tune. "The Old Chieftain To His Sons" was published in 1803 in his Songs, Chiefly in The Scottish Dialect (p. 33). His version was very popular throughout the 19th century. It was regularly reprinted, for example in a popular collection like The Pocket Encyclopedia of Scottish, English, and Irish Songs, Vol. 1 (1816, p. 240) and Robert Chambers' Cyclopedia of English Literature: A Selection of the Choicest Productions of English Authors, Vol. 2, (1851, p. 495). George F. Graham used Boswell's words together with the melody from the Skene Manuscript for his Songs of Scotland With Their Appropriate Melodies (1848, here p. 380 in 1887 edition). Even Helen K. Johnson included it in 1889 her Our Familiar Songs (p. 649) and she noted that this was still the "most familiar version".

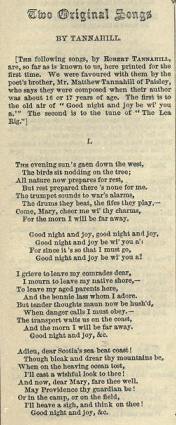

Other poets and songwriters also created new lyrics. Young Robe rt Tannahill based the first of two "Original Songs" on this model. He wrote it around 1790 when he "was about 16 or 17 years of age". The text came to light only posthumously when it was published in Alexander Whitelaw's Book of Scottish Song (1855, p. 15, also in Complete Songs and Poems, 1877, p. 62). rt Tannahill based the first of two "Original Songs" on this model. He wrote it around 1790 when he "was about 16 or 17 years of age". The text came to light only posthumously when it was published in Alexander Whitelaw's Book of Scottish Song (1855, p. 15, also in Complete Songs and Poems, 1877, p. 62).

Interestingly Gavin Greig collected in September 1907 a short song that combines the first four lines of Tannahill's poem with the couplet about the "departing night" (No. 1532, Vol. 8, p. 44):

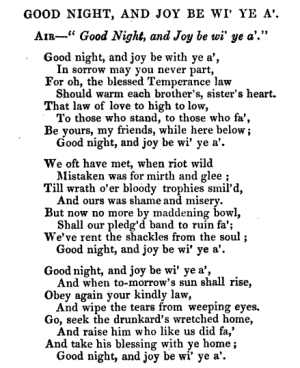

The evening sun goes down the west,

The birds sit nodding on the tree;

All nature now prepares to rest,

But there's no rest prepared for me. Guid-nicht and joy, guid-nicht and joy

Guid nicht and joy be wi' ye a'

For this is my departing nicht,

And the mourn's the day I'm gaun awa'.

Joanna Baillie's  "Good Night, Good Night!" was included in 1825 in Allan Cunningham's The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 4 (p. 212). James Hogg called his version "Good Night And Joy" and it was used as the last song of R. A. Smith's Scottish Minstrel (Vol. 4, 1823, p. 104, at the Internet Archive, reprinted in The Poetical Works of the Ettrick Shepherd, Vol. 5, 1840, p. 208). Amusingly the tune was even appropriated by the Temperance movement. This variant can be found in Edwin Paxton Hood's Book of Temperance Melody (1850, p. 63). "Good Night, Good Night!" was included in 1825 in Allan Cunningham's The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 4 (p. 212). James Hogg called his version "Good Night And Joy" and it was used as the last song of R. A. Smith's Scottish Minstrel (Vol. 4, 1823, p. 104, at the Internet Archive, reprinted in The Poetical Works of the Ettrick Shepherd, Vol. 5, 1840, p. 208). Amusingly the tune was even appropriated by the Temperance movement. This variant can be found in Edwin Paxton Hood's Book of Temperance Melody (1850, p. 63).

V.

More important for the further development of the song was another text, this time by anonymous street-poet. It can be found in a Scottish chapbook:

- Four songs: The scolding wife. The sorrowful man at peace. The Sheffield 'prentice. Good night and joy be with you all, Printed by Thomas Duncan, 159, Saltmarket, Glasgow [1815-1822?] (National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, RB.s.2664(09), see also Copac; during these years Duncan had a shop at this address, see Scottish Book Trade Index, available at the NLS)

This is in fact the earliest available precursor of the modern "Parting Glass". The first two verses - with only some minor variations - as well as some lines of the fourth would later be used in the Irish song:

All the money e'er I had,

I spent it in good company,

All the hardships e'er I had,

Alas they were to none but me.

From what I've done for want of wit;

My memory I will recal,

I hope to mend it all as yet,

Good night and joy be with you all.

If I had money for to spend,

And time and place to sit awhile,

There is a fair maid in this town,

So fain I would her heart beguile.

Her cherry cheeks, her ruby lips,

alas! she has my heart withal;

Come, give me the parting kiss,

Good night and joy be with you all.

How could I give you that kiss!

To part with your sweet company,

I think my very heart will break,

when I do take my leave of thee.

Be it well, be it woe, whate'er betide,

My darling dear I'll go with you;

My dearest dear, you'll think on this,

when I am far away from you.

But now the time is drawing near,

when here no longer I can stay,

There was ne'er a comrade ever I had,

But was sorry at my going away.

But since it's happened so with me,

That you're to rise and I'm to fall,

Come give me the parting glass,

Good night and joy be with you all.

But the author of this text also must have been familiar with the original words to "Neighbours Farewell To His Friends". The first four lines of the fourth verse are clearly a variant of the first half of the old song's first verse:

Now come is my departing time,

And here I may no longer stay,

There is no kind comrade of mine

But will desire I were away.

Also the lines 2 to 6 of the first verse are derived from the corresponding lines of the second verse of "Neighbours Farewel":

[...]

In loving kind good Company;

For all offences I repent,

And wisheth now forgiven to be;

What I have done, for want of wit,

To Memory I'll not recall:

[...]

Good Night, and GOD be with you all

Interestingly two Scottish versions from oral tradition in the Greig-Duncan Collection are clearly influenced by the text from the chapbook (No. 1531, Vol. 8, p. 42 & 43, notes p. 378). One was written down in April 1907 from the singing of Robert Alexander who had learnt it "early from a travelling man" (No.1531B):

O this is my departing night

And the morn's the day I'm gaun awa

Pass round about your parting glass

Good night and joy be wi you a.

But gin I had money for to spend

Or time for to stay here a while

There is a lassie in this house

This very night I wud her beguile.

Her rosy cheeks an ruby lips,

They do my very heart enthrall,

Pass round about your parting glass,

Good night an' joy be wi' you a'.

Her cheeks they're like the roses red,

Her neck, tis like the drifted snaw,

Her eyes were like the violets blue,

That in the month of June do blaw.

But since it's so that I must go

And leave my friends and comrades a',

In case we ne'er may meet again

Good night an joy be wi you a'.

The other one was by William Wallace (No.1531A, November 1911) who had learned it "about thirty-five or forty years ago":

[...]

3. It's how could I gie you the partin' kiss,

Or part from your sweet Company?

I'm sure my very heart would break,

Were I to take my leave o' thee.

But this is my departing night,

And the morn's the day I'm goin' awa,

I'm sure my comrades will be sad,

My rivals glad when I'm awa.

Säe it's ance gweed nicht and twice gweed nicht,

Gweed nicht and joy be wi' ye a';

For I mean to mend my morals yet,

Gweed nicht and joy be wi' ye a'.

Interestingly in both cases the lines about the "departing night" are included. It seems they were widely known and they had even infiltrated another song collected by Greig and Duncan. In "The Lan's And Banks O' Bonny Montrose" they were part of the refrain (No. 1529, Vol. 8, p. 38 - 40):

For it's ance guid-nicht and it's twice guid-nicht,

Guid-nicht and joy be wi' ye a',

For this is my depairting nicht,

And the morn's the day I'm gaun awa'.

But the text from the chapbook also migrated to England as can be seen from a broadside with the title "Good Night And Joy Be With You All" that was printed in Liverpool between 1820 and 1824 (Harding B 25(762), at BBO). The printer's name was Armstrong but I presume he had nothing to do with the Scottish clan:

All the money e'er I had,

I spent it in good company

And all the harm that e’er I did,

I hope excused I will be,

And what I've done for want of wit,

To my memory now I cann't recall,

So fill us up a parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all

If I had money to spend,

Or time and place to stop awhile,

There is a fair maid in the town,

And fain I would her heart beguile,

For her ruby lips and cherry cheeks

Have stole my tender heart away,

So fill us up a parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all

My dearest dear, do not be coy,

Nor treat your love with cold disdain,

For though that I shall go away,

Perhaps I may return again;

And if that I return again,

I will enjoy my own dear lass,

And we will tie the nuptial knot,

At the drinking of a joining lass.

The first two verse are in parts closer to the modern "Parting Glass" but for some reason the third verse is completely different.

VI.

At this point we know that most of the text of the modern "Parting glass" was written in Scotland. When was this song introduced in Ireland? The earliest known Irish version can be found on a broadside published by J. & H. Baird in Cork: "Good Night And Joy Be with you all. A New Song" (Madden Ballads 12, Frame 8341). The exact date of publication is not known but the Bairds were active as printers in Cork during the 1830s (see Moulden 2011, p. 609):

All the Money that e'er I had,

I spent it in good company,

And all the hardships that e'er I past,

I past them for the loss of thee.

If had money at my will,

Time and place to sit awhile,

There's a fair girl in this town,

and fain I would her beguile,

Her cherry cheeks and ruby lips,

Alas! she has my heart betray'd,

Come give to me that parting kiss,

Good night and joy be wi' you a'.

What I done its for want of wit,

And to my mem'ry I will recall,

I hope we'll all be good friends yet,

Good night and joy be wi' you a'.

But now the time is coming on,

When I my derest girl must go,

I think my heart will break,

At thoughts of parting you my dear.

But be it well or be it ill,

What e'er will betide my darling girl,

My dearest dear I'll go with you,

And you'll thinkof me when far awa',

Come fill me that parting glass,

Good Night and joy be wi'you a'.

But now the time is drawing near,

When your to kiss and I'm to fa',

Come give to me that parting kiss,

Good night and joy be wi' you a'.

This variant was surely derived from the Scottish chapbook text. For some reason it has a very unusual structure: two verses of 12 lines and two of four lines, perhaps a kind of refrain. But there are some variations compared to the original version that can't be found in later versions of "The Parting Glass" and it is obvious that Baird's text had no influence on the song's further development.

Much more important was another broadside published at least a decade later: "A New Song caled [sic!] the Parting Glass", printed by W. Birmingham, 103 Thomas-street, Dublin (Madden Ballads 12, Frame 8667). This version is also based on the text from the chapbook. Two verses have only minor edits while the other two saw more variations. The first three verses are now more or less as we know them today. But for some reason this variant also had a chorus that was later dropped.

All the money that e’er I had,

I spent it in good company.

And all the harm ever I done,

Alas! it was to none but me,

And all I have done for the want of wit,

To memory now I can't recall,

So fill to me the parting glass,

Good night and joy be with you all.

Chorus:

Be with you all, be with you all

Good night and joy be with you all

So fill to me the parting glass,

Good night and joy be with you all.

All the comrades that e’er I had,

They’re sorry for my going away,

All the sweethearts e’er I had,

They’d wish me one day more to stay,

But since it came unto me lot,

That I should rise and you should not,

I gently rise and with a smile,

Good night and joy be with you all.

If I had money enough to spend,

And leisure time to sit awhile,

There a fair maid in this town

That sorely has my heart beguiled,

Her rosy cheeks and ruby lips,

I own she has my heart enthralled;

Then fill to me the parting glass,

Good night and joy be with you all.

When I‘m boosing at my quait

And none but strangers round me all

My poor heart will surely break,

When I’m boosing far awa,

Far awa, oh, far awa;

When I am boosing far awa,

My poor heart will surely break,

When I’m boosing far awa.

Unfortunately it is not clear when this broadside was published. Printer Walter Birmingham had a shop in Queen Street on Dublin from at least 1842 to 1847 (see Pettigrew & Oulton's Dublin Directory 1842, p. 420, at Failte Romhat; Slater's Commercial Directory of Ireland 1846, p. 56, at Failte Romhat; Dublin Almanac 1847, p. 454). Between 1849 and 1854 he was at 92 Thomas Street (according to Brown, Glimpses, No. 5, see also Thom's Directory of Ireland 1850, p. 812) and in 1862 he could be found at 3 Mullinahack (see Dublin Street Directory 1862 at Library of Ireland) But I haven't been able to find out when exactly he lived at 103 Thomas Street. It could have been 1848, the year before he moved to 92 Thomas Street or the years afterwards, 1855 to 1861.

Also it is not definitely known if he really was the first one to publish this variant in Ireland. Catherine Haly in Cork also brought out a broadside with the title "A new song called The Parting Glass". In the catalogue of the library of the Trinity College in Dublin it is tentatively dated as from "c. 1860". But Haly was busy as a printer in Cork since the mid-40s (see Moulden 2011, p. 610) and it is surely possible that she has introduced this song in Ireland. Her text is nearly identical to the one printed by Birmingham as can be seen from another edition only called "The Parting Glass" that is available at the allegro Catalogue of Ballads (Harding B26(499), on the right, at BBO).

Interestingly there is one more broadside with another variant of "The Parting Glass". This one has more or less the same text as the versions published by Walter Birmingham and Catherine Haly but also two additional verses (Harding B 26(498), on the left, at BBO). Unfortunately there is no imprint and we know neither the printer nor the year of publication. This could also have been the original Irish version. The biggest problem is often enough to find out when a particular broadside was published. Without this basic information it is quite difficult to construct a reliable chronology.

It would be also be interesting to know why this song was published in Ireland at that time, a couple of decades after the original text had been printed in Scotland. Perhaps it was brought over by an anonymous singer who was familiar with the the chapbook and then made up his own version. But I wouldn't exclude the possibility that the publisher - whoever it was - or one of their hired street-poets simply dug out this Scottish oldie, edited it a little bit and then tried to sell it it as a "new song". But as usual there is much more that we don't know than what we know.

A version with four verses was also printed by Nugent & Co. from Dublin on some broadsides with the title "An admired Song called The Parting Glass" (2806c.15(13), 2806c.15(114), Harding B 19(89), all at BBO; also without imprint Madden Ballads 12, Frames 8621 & 8712). In the allegro Catalogue they are dated as from 1850 - 1899. That's not very helpful. In the catalogue of the National Library of Ireland "1865?" is given as a possible year of publication. This text has some printing errors and some minor edits. For example in line 5 of verse 1 "want of wit" has been changed to "want of sense" and the "fair maid" in the third verse has been turned into a "girl". The fourth verse has some more variations. These changes suggest that Nugent's broadsides were printed after Haly's and Birmingham's.

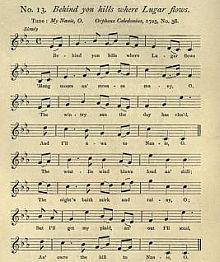

Interestingly on Nugent's broadsides the tune is noted: "Air: - Over the hills to my Nanny, O". This refers to another song by Robert Burns, "My Nannie, O" (1787, see Dick, No. 13, p. 12 and One Hundred Songs of Scotland, p. 29; the version in SMM VI, No. 580, p. 600 is set to a different melody; Burns had borrowed the tune from an older popular song with the same title. It had been first printed in William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius in 1725 and 1733, No. 38, see also SMM 1, No. 88, p. 89 )

Behind yon hills where Lugar flows,

'Mang moors an' mosses many,

O, The wintry sun the day has clos'd,

And I'll awa to Nanie, O.

The westlin wind blaws loud an' shill;

The night's baith mirk and rainy, O;

But I'll get my plaid an' out I'll steal,

An' owre the hill to Nanie, O. [...]

It's not clear if this melody and the text of "The Parting Glass" were were combined in Ireland or already earlier in Scotland or England. The broadside from Liverpool doesn't mention a tune. At least it is interesting to note that the Irish song "The Parting Glass" at this time consisted of a tune imported from Scotland and a text that also for the most part had been created there.

VII.

Now we have all three verses of the modern version of "The Parting Glass". Only the melody is missing. The British Folklorists are not of much help in this respect. They have mostly avoided this song. Only Greig & Duncan have collected the two variants from Scotland that I have already mentioned. Version B "nearly coincides with the air in Johnson ['s SMM] in its first strain" while version A is quite different.(No. 1531, Vol. 8, p. 43, notes p. 378) None of them resembles in any way the tune we are looking for.

There are also some great collections of Irish tunes that are worth checking out. Petrie's Complete Collection of Irish Music (1902, No. 920, Vol. 2, p. 233) includes a piece called "Good Night, Good Night, And Joy Be With You" but this is again very different and doesn't help much. But two tunes in O’Neill's Music of Ireland (1903) - "The Parting Glass" (No. 58, see abcnotation.com) and "Burn’s Farewell" (No. 269, see abcnotation.com and Fiddler’s Companion) - are clearly variants of the one used for the modern version of "The Parting Glass".

Even more successful is a look into P. W. Joyce's Old Irish Folk Music And Songs (1909). "Sweet Cootehill Town" (No. 384, p. 192) is sung to the same melody as "The Parting Glass". It's a farewell song of emigrants leaving their hometown for a new life in America:

Joyce - born in 1827 - had learned it "when a mere child":

"The air belongs I think to Munster; for I heard it played and sung everywhere, and quite often with other words besides 'Sweet Cootehill Town' It is sometimes called "The Peacock," which is certainly not its original name. Versions of it have been published in [R. A.] Smith's‘[The Irish Minstrel.] Vocal Melodies of Ireland [1825, p. 68, as tune for the song "My Mary, When The Twilight Still" ]’ and elsewhere [...] In Cork and Limerick the people often sang to it Burns's song Adieu, a heart-warm fond adieu' so that it was commonly known by the name of 'Burns's Farewell'[...] The air seems to have been used as a general farewell tune, so that [...] it is often called 'Good Night And Joy Be With You All'" (p. 191/192)

According to Bruce Olson's Early Irish Tune Title Index a tune with the title "The Peacock" was first published in James Aird's A Selection of Scots, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol. 2 (1782, No. 17, p. 6; tune available at Fiddler's Companion: The Peacock [3] and abcnotation.com):

The tune was later included in at least five other collections:

- Smollett Holden, A Selection Of Masonic Songs, Dublin 1798 (as "Farewell [by the late celebrated BVr. R. Burns]", see SITM I, No. 3237, p. 586).

- Smollett, Holden, A Collection of Old Established Irish Slow and Quick Tunes', Vol. 1, Dublin ca. 1805, p. 17

- Smollett Holden, A Collection of the Most Esteem'd Old Irish Melodies, Vol. 2, Dublin ca. 1807/8, p. 41

- P. O' Farrell's Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, Vol. 4 (i. e. Vol. 2), London ca. 1810, p. 12, see abcnotation.com)

- S. T. Colclough's New and Complete Instructions for the Union Pipes, Dublin 1820, p. 21, as "Burn’s Farewell"

It seems that it was very popular in Ireland. There are four songs in Sam Henry's Songs of the People - collected between 1924 and 1937 - that use variants of the tune (Huntington & Hermann, pp. 127, 158, 221, 299). A version of "The Parting Glass" from August 1938 (p. 65) is also quite interesting because it has retained some elements known from both the Liverpool broadside and the Scottish chapbook. This strongly suggests that these text were also known in Ireland.

But only 30 years after the publication of Joyce’s "Sweet Cootehill Town" the modern version of "The Parting Glass" - without the refrain and the additional verses but with this particular melody - was printed for the very first time in Colm O Lochlainn's Irish Street Ballads (1939, No. 69, p. 138). O Lochlainn writes in his notes (p. 225) that his mother had learned it from his "grandfather, John Carr of Limerick" but he also refers to Joyce's "Sweet Cootehill Town" and names as the source for the lyrics both his mother and a broadside. It must have been a broadside published either by Haly or Birmingham because his text doesn't include the edits and errors of Nugent's variant from Dublin.

This "Parting Glass" is virtually identical to the version recorded by the Clancys in 1959 and it is not unreasonable to assume that they have learned it - directly or indirectly - from this book. In fact only the publication in O Lochlainn's Irish Street Ballads and then the recording by the Clancy's have established this variant as the "definitive" version of "The Parting Glass".

During the Folk Revival era this song was also recorded by some other artists:

- Patrick Galvin, Irish Drinking Songs (1957?, Riverside RLP 12-604)

- Robin Roberts: Come All ye Fair and Tender Ladies (1959, Tradition TLP 1033, see the short review in Billboard, 29.6.1959)

- Tom Kines, An Irishman In North America (1962, Folkways FW 03522; this is based not on the Clancy's version but on a field recording from Newfoundland by Kenneth Peacock in 1952)

- Ann Mayo Muir, Magic of Mayo Muir (1963, 20th Century Fox TFM 3122)

Galvin's may have been the very first recording of "The Parting Glass" but by all accounts the Clancy Brothers' version turned out to be the most influential.

Bob Dylan also learned this song from the Clancys. It was the model for his own "Restless Farewell" (1963, on The Times They Are A-Changin'; lyrics at BobDylan.com). He used the "song's harmonic structure and sentiment" (Harvey, p. 94/5), varied the melody a little bit and - following in the footsteps of Burns, Boswell & co - wrote his own words. It's surely not among his best songs and only two live performances from the 60s are known. But Frank Sinatra liked this song and asked Dylan to perform it at the concert celebrating his 80th birthday in 1995. Bob Dylan then only played it live one more time in 1998 a day after Sinatra's death.

Today "The Parting Glass" has superseded all other songs from this family. Sir Alexander Boswell's version for example had been so popular during the 19th century but today it is barely known. In the end - and once again - the work of anonymous street poet has won over the products of notable songwriters like Boswell or Robert Burns and an Irish melody of unknown origin has pushed aside an even older tune that had been immensely popular for nearly 300 years.

Credits

- Many thanks to Stewart Grant who wrote about this song in 2007 for my former website morerootsofbob.com.

- I also wish to thank the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, for sending me a pdf-scan of the Scottish chapbook Four songs: The scolding wife. The sorrowful man at peace. The Sheffield 'prentice. Good night and joy be with you all, Printed by Thomas Duncan, 159, Saltmarket, Glasgow [1815-1822?] (RB.s.2664(09))

Illustrations & Images

- "The Parting Glass", image and midifile created with MC Musiceditor (programm available at mcmusiceditor.com) from tune in abc notation found at abcnotation.com , text from mudcat.org.

- From: William Dauney, Ancient Scotish Melodies: From a Manuscript of the Reign of King James VI, Edinburgh 1838, p. 222, source: The Internet Archive, midi-file created with MC Musiceditor.

- "Good Night And God Be With You", from Henry Playford, A Collection Of Original Scotch Tunes, London 1700, p. 4 source: The Internet Archive, midi-file created with MC Musiceditor.

- From: William McGibbon, A Collection of Scots Tunes, London ca. 1755, p. 120, source: pdf-file downloaded from IMSLP.

- "Good Night and Joy be wi’ ye a’", from Niel Gow, Part Second of the Complete Repository, of Original Scots Tunes, 1802; image and midi-file created with MC Musiceditor from tune in abc notation found at The Fiddler's Companion

- From: David Herd, Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1776, p. 225, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Sir Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Vol. 1, London 1802, 5fth edition, 1821, p. 287, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Peter Buchan, Ancient Ballads And Songs Of The North Of Scotland, Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1828, reprint 1875, p. 121, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Complete Works of Robert Burns, Vol. 5,New York 1909, p. 54, source: The Internet Archive

- From: James C. Dick (ed.), The Songs of Robert Burns, London 1903, p. 214, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Robert Chambers, The Scottish Songs, Vol. 1, Edinburgh 1829, p. 80, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Alexander Whitelaw, The Book of Scottish Song, Glasgow 1855, p. 15, source: The Internet Archive

- From: Edwin Paxton Hood (ed.), The Book of Temperance Melody, 2nd edition, London 1850, p. 63, source: Google Books

- From: From: James C. Dick (ed.), The Songs of Robert Burns, London 1903, p. 12, source: The Internet Archive

- Tune and text from P. W. Joyce, Old Irish Folk Music And Songs. A Collection Of 842 Irish Airs And Songs, p. 192; score and midi-file created with MC Musiceditor

- "The Peacock", from: James Aird, A Selection of Scots, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol. 2 , first published 1782 ( this edition was possibly a later reprint of Vol. 1 & 2) No. 17, p. 6, source: pdf-file downloaded from The Internet Archive (midi-file created with MC Musiceditor)

Literature & Online Resources

- abcnotation.com

- BBO = Broadside Ballads Online (Bodleian Libraries)

- Sir Alexander Boswell, Songs, Chiefly In The Scottish Dialect, Edinburgh 1803 (available at Google Books)

- Peter Buchan, Ancient Ballads And Songs Of The North Of Scotland, Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1828 (reprint 1875 available at The Internet Archive)

- Robert Burns, Complete Works, Vol. 5, New York 1909 (available at The Internet Archive)

- Robert Chambers, The Scottish Songs, Vol. 1, Edinburgh 1829 (available at The Internet Archive)

- William Christie, Traditional Ballad Airs, Vol. I, Edinburgh 1876 & Vol. II, Edinburgh 1881 (available for download as pdf-files at http://www.celtscot.ed.ac.uk/ballad.htm (University of Edinburgh, Celtic & Scottish Studies))

- Allan Cunningham, The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 4, Lodon 1825 (available at The Internet Archive)

- James C. Dick (ed.), The Songs of Robert Burns, London 1903 (available at The Internet Archive)

- William Dauney, Ancient Scotish Melodies: From a Manuscript of the Reign of King James VI, Edinburgh 1838 (about the Skene Manuscript; available at The Internet Archive)

- English Broadside Ballad Archive (UCLA, Santa Barbara)

- ESTC = English Short Title Catalogue (British Library)

- Aloys Fleischmann, Sources Of Irish Traditional Music, C. 1600 - 1855, Vol. I, New York & London 1998 (= SITM)

- Oliver Goldsmith, The Miscellaneous Works, ed. by James Prior, Vol. 1, London 1837 (available at Google Books)

- George F. Graham, The Popular Songs of Scotland with Their Appropriate Melodies, Edinburgh 1887 (first published 1848; available at The Internet Archive)

- Todd Harvey, The Formative Dylan. Transmissions And Stylistic Influences, 1961 - 1963, Lanham, Maryland & London 2001

- T. F. Henderson (ed.), Sir Walter Scott's Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Vol. 2, Edinburgh, London & New York 1902 (available at The Internet Archive)

- David Herd, Ancient And Modern Scottish Songs, Vol. 2, Edinburgh 1776 (available at The Internet Archive)

- James Hogg, The Poetical Works of the Ettrick Shepherd, Vol. 5, London 1840 (available at Google Books)

- Edwin Paxton Hood (ed.), The Book of Temperance Melody, 2nd edition, London 1850 (available at Google Books)

- Gale Huntington & Lani Herrmann (ed.), Sam Henry's Songs Of The People, Athens, GA 1990

- Irish Music Collections Online (=IMCO) [not available anymore]

- P. W. Joyce, Old Irish Folk Music And Songs. A Collection Of 842 Irish Airs And Songs, Hitherto Unpublished, Dublin 1909 (available at The Internet Archive, but not in good quality)

- Helen Kendrick Johnson, Our Familiar Songs And those Who Made Them, New York 1889 (online at: The Internet Archive)

- James Johnson, The Scottish Musical Museum, Vol. 1, London 1787 (later edition from 1853 available at Google Books)

- James Johnson, The Scottish Musical Museum, Vol. 6, London 1803 (later edition from 1839 available at Google Books)

- Jane Keefer, Folk Music - An Index To Recorded Sources

- Calm O Lochlainn, Irish Street Ballads, Dublin 1993 (here quoted after The Complete Irish Street Ballads, London & Sydney 1984)

- The Madden Ballads. Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Songs and Ballads from the Cambridge University Library, 12 Volumes, Woodbridge, CT 1987 (Microfilm)

- William McGibbon, A Collection of Scots Tunes, London ca. 1755 (available at IMSLP)

- John Moulden, Popular Songs, in: James Murphy (ed), The Oxford History Of The Irish Book, Volume IV: The Irish Book In English 1800 - 1891, Oxford & New York 2011, pp. 602 - 611

- Bruce Olson, Early Irish Tune Title Index

- Bruce Olson, An Incomplete Index Of Scottish Popular Song And Dance Tunes Printed In The 18th Century

|

|

|

More Song Histories

|

|

|

- Bruce Olson, More Scarce Songs: "Good Night And Joy Be With You All"

- Francis O’Neill, O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, 1903 (available at Freesheetmusic.net )

- One Hundred Songs of Scotland: Words and Music, San Francisco 1859 (available at Google Books)

- George Petrie & Charles Villiers Stanford (ed), The Complete Collection of Irish Music, Vol. 2 London, 1902 (available at IMSLP)

- The Pocket Encyclopedia of Scottish, English, and Irish Songs, Glasgow 1816, Vol. 1 (available at Google Books

- Scotmus.com: The Skene Manuscript & Playford's Scotch Tunes [this site is now unavailable]

- Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Vol. 1, London 1802 (5fth edition, 1821 available at The Internet Archive)

- Patrick Shuldham-Shaw, Emily B. Lyle & Katherine Campbell (ed.), The Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection, Vol. 8, Aberdeen 2002

- Alexander Whitelaw, The Book of Scottish Song, Glasgow 1855 (available at Google Books)

First posted here in November 2010, revised version posted on March 30, 2012

Comments: Please use my blog, send a mail to info[at]justanothertune.com

© Jürgen Kloss

November 2010/March 2012

|